WHAT ARE THE DIMENSIONS OF DISTRICT CAPACITY THAT ENABLE EFFECTIVE EVIDENCE-BASED DECISION-MAKING?

Much of the discourse around building practitioners’ “capacity” to use research evidence presumes that external partners produce research for which practitioners need to increase their knowledge and skill to use it effectively. This implies a unidirectional, narrow view of “translating” research into practice which neglects the range of roles, processes, and evidence types involved in the full scope of practitioners’ evidence-based decision-making (EBDM). The broader perspective proposed here highlights four critical distinctions:

- First, an organization’s capacity goes beyond just the sum of the capabilities (knowledge and skills) of the individuals within the organization, and includes important system-level structures and resources, such as data and knowledge management infrastructure or social processes for decision-making, which affect the reliability and quality of EBDM.

- Second, research is only one form of inquiry producing rigorous, useful evidence for educational agencies; evaluation and improvement provide valuable methods addressing other important goals and incorporating other forms of evidence (more on how these categories differ below).

- Third, the use and generation of evidence are distinct activities requiring different elements of EBDM capacity.

- Fourth, such evidence may be generated from sources that are internal to the organization, not just from external researchers.

Understanding the importance of these distinctions first demands articulating districts’ EBDM goals, to define success. We would not expect a district to use evidence for its decision-making if high-quality evidence exists but is not relevant, or if the relevant evidence available is of dubious quality. Whether evidence is relevant to a district’s decision depends on its decision-making goals.

Three types of questions that guide EBDM

We can conceptualize the questions that guide decision-making in three categories: research, evaluation, and improvement [1]. I adopt the narrower definition of research [2] here both for its familiarity and for its value in distinguishing between broadly generalizable results and locally specific results. Thus:

Research questions elucidate the desired state and how to measure it. Answering these questions may include consulting the literature for generally applicable theoretical approaches and robust empirical evidence, as well as conducting new analyses which may potentially apply to other contexts.

Evaluation questions assess gaps between the current and desired states. These focus on analyzing local needs and program effectiveness. While some evaluations may be sufficiently generalizable to also count as research, their primary purpose for the local agency is to understand the function or impact of a particular program.

Improvement questions examine how to develop, discover, or optimize strategies for closing gaps between the current and desired states. These explore changing conditions and actions for better product design or service delivery. Some improvement projects may overlap with formative and developmental evaluations of pilot interventions; some design studies or implementation studies of improvement initiatives may also offer opportunities for research if there is broader interest in documenting and learning from these processes to apply elsewhere.

Situating the goals within the work of an educational agency

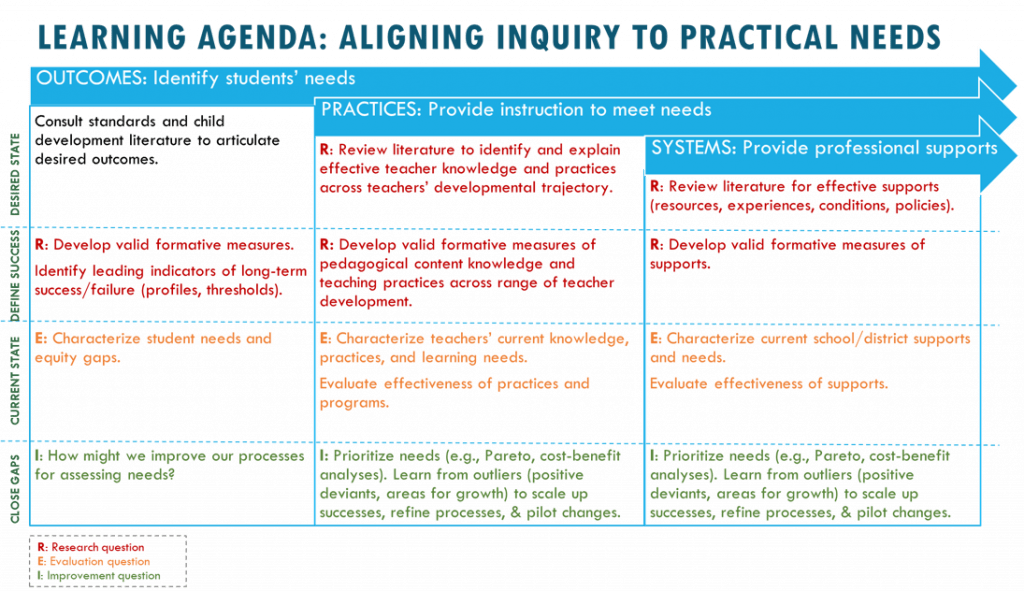

Most urgently, educational agencies must serve their students better, which drives their need for information and action. I offer a simplified framework for how addressing research, evaluation, and improvement questions can inform district-wide decision-making across the following three levels:

- Outcomes: Identify students’ needs

- Practices: Provide services to meet those needs

- Systems: Strengthen structures and professional supports for providers to meet those needs

Some of the questions that emerge at these levels invite research, while others motivate evaluation, and still others are simply improvement questions. Figure 1 depicts the application of this framework to instruction.

Figure 1. A framework for constructing a learning agenda that encompasses research, evaluation, and improvement questions, across student outcomes, teacher practices, and system-level supports.

For example, if the targeted outcome is students’ sense of belonging, then developing valid instruments and determining early indicators of belonging are possible research questions where external partners can contribute valuable expertise. Characterizing different subgroups’ relative sense of belonging would constitute an evaluation question most relevant to the local context. Similarly, elucidating the specific obstacles impeding a district’s process of administering surveys and locating students experiencing homelessness would address a local improvement need that is less likely to yield implications for the broader research community.

At the practices level, determining which strategies best develop students’ phonological decoding skills or assessing teachers’ understanding of common mathematical errors is a research question, while determining whether a particular socioemotional learning program has been implemented effectively is a traditional evaluation question. In contrast, characterizing the variability in how teachers deliver feedback or developing procedures to ensure consistent progress monitoring of focal students would address improvement questions.

Similarly, at the systems level, identifying essential leadership supports or effective coaching techniques would be a research question, while measuring the effectiveness of their delivery is an evaluation question, and understanding what impedes the district in aligning and coordinating its resources is an improvement question.

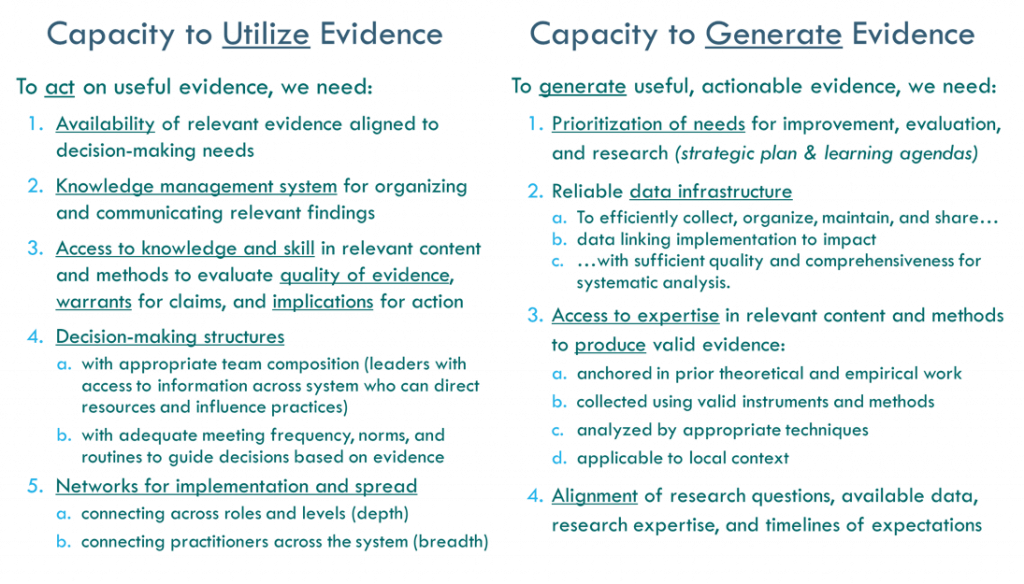

Capacities for EBDM

In all of these cases, EBDM requires the capacity to locate and utilize relevant evidence, and potentially also the capacity to generate useful evidence if none presently exists. Although research-practice partnerships (RPPs) have tended to privilege the generation of new research evidence, whether by external researchers or in co-production with practitioners, building the capacity to utilize existing evidence offers a greater return on both past and future investments in the evidence generated by any entity. Once established, the structures and resources required for utilizing evidence apply to both existing and new evidence, whereas generating new evidence demands additional time and support. Figure 2 enumerates the necessary conditions, resources, and structures constituting the capacities to utilize and to generate evidence.

Figure 2. Components of system-wide capacities to utilize and to generate evidence.

The most important prerequisite for districts to act on useful evidence is the availability of relevant evidence aligned to their decision-making needs (as illustrated in Figure 1). Utilizing such evidence also requires having a knowledge management system for finding it, as well as access to expertise to ensure valid interpretations of the findings when formulating implications for action. Decision-making structures are critical for collectively sharing, interpreting, and applying the evidence to the district’s local context, in conjunction with networks of leaders and practitioners who are empowered to act on and spread practical knowledge.

In the absence of sufficient relevant evidence, a district seeking to engage in EBDM must be able to lead or co-lead its own inquiry and analysis in order to generate useful evidence (see column 2 of Figure 2). This type of capacity depends on developing a useful research, evaluation, and improvement agenda to prioritize its inquiry needs and guide projects toward those needs. Conducting analyses requires a reliable data infrastructure for providing comprehensive, high-quality data suitable for analysis; access to expertise in the relevant content and methodological areas to produce valid evidence; and alignment between the inquiry questions, available data, content and methodological expertise, and timelines of expectations.

The capacity to sustain evidence-based practices spans both the utilization and generation of evidence, requiring ongoing processes for monitoring and adapting practices to ensure that the implementation of policies achieves the desired impact.

EBDM processes in action

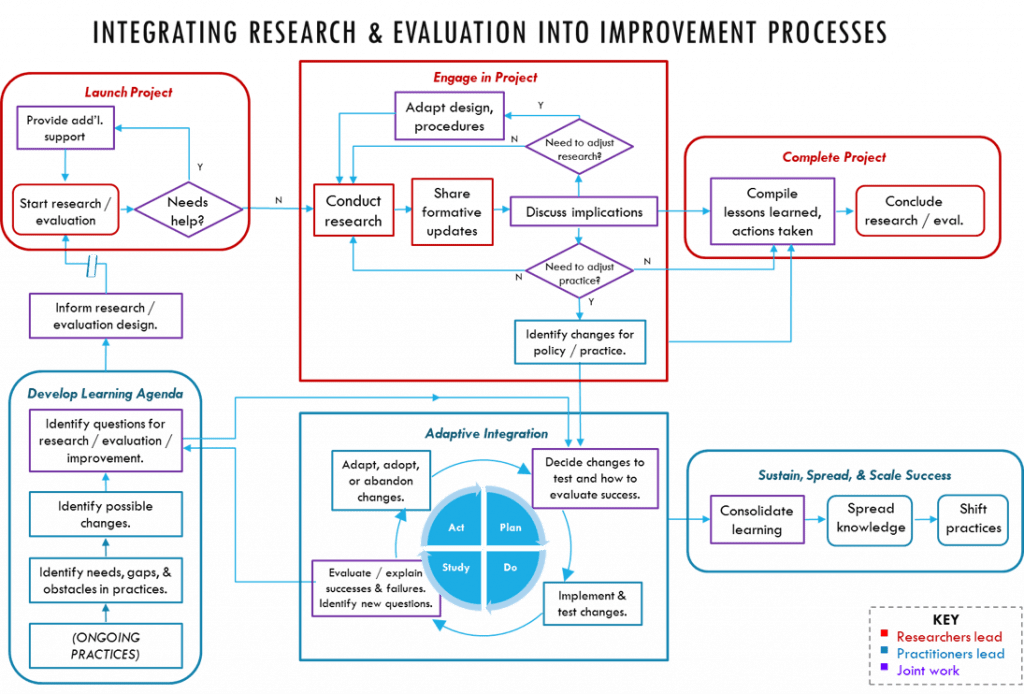

Integrating EBDM in practice draws upon the capacities to utilize and generate evidence described above throughout a district’s process from inquiry to implementation. Figure 3 illustrates how a district might productively integrate the generation of new evidence with the improvement processes required for successful implementation of evidence-based practice. The initial stage (lower left) of formulating the learning agenda guides the search for relevant evidence, whether from the literature or from new data collection (top row). Those findings then inform the potential changes to be tested in practice, through cycles of continuous improvement (lower middle). Whereas research or evaluation projects typically culminate in disseminated reports (upper right), successful improvements demonstrate their viability through institutionalized learning and sustained changes to practice at scale (lower right).

Figure 3. Flowchart depicting activities to support research and evaluation projects on the top, with the improvement processes necessary to guide and integrate learning in practice as the foundation underneath.

While this diagram highlights projects generating new evidence, similar processes may apply to literature searches, except writing the review likely precedes exploring implications for action. The diagram also does not distinguish between external and internal research projects. For external projects, such as what might occur within a research-practice partnership, coordinating productive collaborative inquiry requires another set of conditions: communication, trust, flexibility, and compatibility between internal (practitioner) and external (researcher) partners [3]. Discovering and developing these conditions requires not just the good fortune of alignment of interests and availability, but also significant time and resources [4]. This motivates better understanding when it is worthwhile to nurture external partnerships, and when it is more efficient to allocate resources to generate the evidence internally, which I discuss next.

Generating evidence using internal vs. external expertise

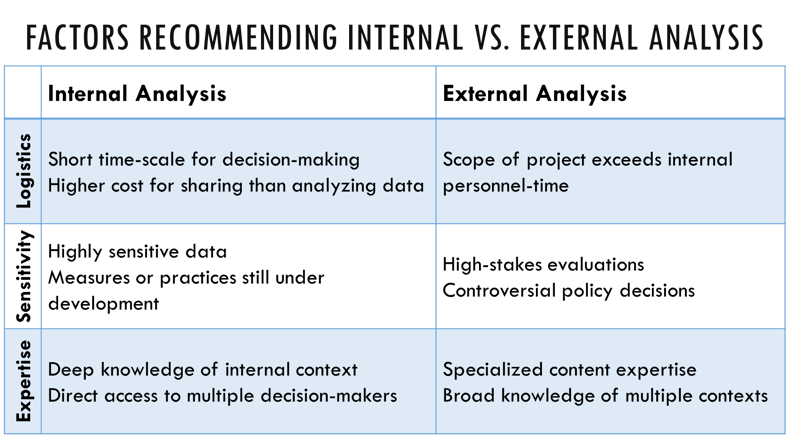

Certain logistical constraints may point toward internal analysis, such as a short timescale for decision-making or circumstances where it is easier to conduct the analysis than to anonymize, link, and share the data with an external partner. Alternatively, a large project scope that exceeds the agency’s available personnel-time may justify external engagement. Internal analyses may be preferable when analyzing data with high sensitivity, such as narrative descriptions in disciplinary referral records or special education assessment reports, or early-stage measures that may be useful for informing internal improvement but lack sufficient validation for external research [5]. In contrast, high-stakes evaluations or controversial policy decisions may demand external independence. A final consideration is the nature of relevant expertise: Decision-making goals where direct internal knowledge and access strengthens the opportunity both to explore and to act quickly on the knowledge may motivate internal investigation, whereas questions that benefit from specialized content expertise and knowledge of the broader field may recommend external research. Together, these dimensions highlight the important role for considering factors supporting internally- vs. externally-generated evidence to guide districts’ decision-making (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Possible factors motivating internal vs. external analyses.

An example illustrates the potential interplay of these dimensions. Initiatives with a high funding profile involving calibrated observations and anonymous interviews of a large sample of classroom teachers may be better suited for external evaluators who do not know the individual teachers and have limited access to their colleagues, thereby preserving the staff’s coaching or supervisory relationships. These may be complemented by internal analyses of longitudinal student-level outcome data across different dosages or conditions. The results of both analyses may be integrated into practice through cycles of continuous improvement where internal facilitators support the collection and interpretation of formative data to guide ongoing modifications and monitoring of practice.

Conclusion

These four dimensions highlight the need for a broader conception of “research use capacity.” Beyond creating a more complete picture of the lifecycle of how evidence informs decision-making, this reveals the range of systems, structures, and processes necessary for that cycle to function. Establishing those supporting conditions is critical if we expect evidence to be incorporated effectively in improving educational outcomes.

Norma Ming is Supervisor of Research at the San Francisco Unified School District.

[1] Improvement here comprises quality improvement, continuous improvement, or improvement science, e.g.:

Langley, G. J., Moen, R., Nolan, K. M., Nolan, T. W., Norman, C. L., & Provost, L. P. (2009). The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organizational Performance. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons.

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to Improve: How America’s Schools Can Get Better at Getting Better. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Education Press.

[2] Some may define research broadly, as in “applying systematic methods and analyses to address a predefined question or hypothesis” (http://wtgrantfoundation.org/grants/research-grants-improving-use-research-evidence). Traditional conceptions of research conform to the Common Rule: “a systematic investigation, including research development, testing and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge” (https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/regulations/common-rule/index.html). That expectation of generalizability omits accountability reporting and evaluations conducted only for local progress monitoring, as well as quality improvement efforts focused on understanding or improving implementation of practices (https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/guidance/faq/quality-improvement-activities/index.html).

[3] Henrick, E.C., Cobb, P., Penuel, W.R., Jackson, K., & Clark, T. (2017). Assessing Research-Practice Partnerships: Five Dimensions of Effectiveness. New York, NY: William T. Grant Foundation. https://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2017/10/Assessing-Research-Practice-Partnerships.pdf

[4] Oliver, K., Kothari, A., & Mays, N. (2019). The dark side of coproduction: do the costs outweigh the benefits for health research? Health Research Policy and Systems, 17:33. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-019-0432-3

[5] Solberg, L.I., Mosser, G., & McDonald, S. (1997). The three faces of performance measurement: Improvement, accountability, and research. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality Improvement, 23(3), 135-147. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1070-3241(16)30305-4

Suggested citation: Ming, N. (2019). What Are The Dimensions of District Capacity That Enable Effective Evidence-Based Decision-Making? NNERPP Extra, 1(2), 6-11. https://doi.org/10.25613/AB9J-YF37