WHAT YOU REALLY NEED TO KNOW ABOUT STARTING AN RPP

INTRODUCTION

What are the essentials for starting a research-practice partnership (RPP)? In the fall of 2022, the American Institutes for Research® conducted a landscape analysis and a series of interviews with education RPP leaders from across the country to understand what is needed to start a new RPP [1]. Our study team sought to gather diverse perspectives, interviewing RPP leaders from research-side institutions, practice-side partners in state agencies and school districts, researchers who study RPPs, and funders who have provided grants to establish and develop RPPs. This purposeful sample included 18 individuals with extensive experience in launching and sustaining RPPs, including those who were more recently involved with launching and forming RPPs. Following semi-structured interviews lasting 45–60 minutes each, we used inductive coding to identify themes in their responses, using Henrick et al.’s (2017) five dimensions framework of effective RPPs as guiding organizational themes. Seven themes emerged, which we explore further below.

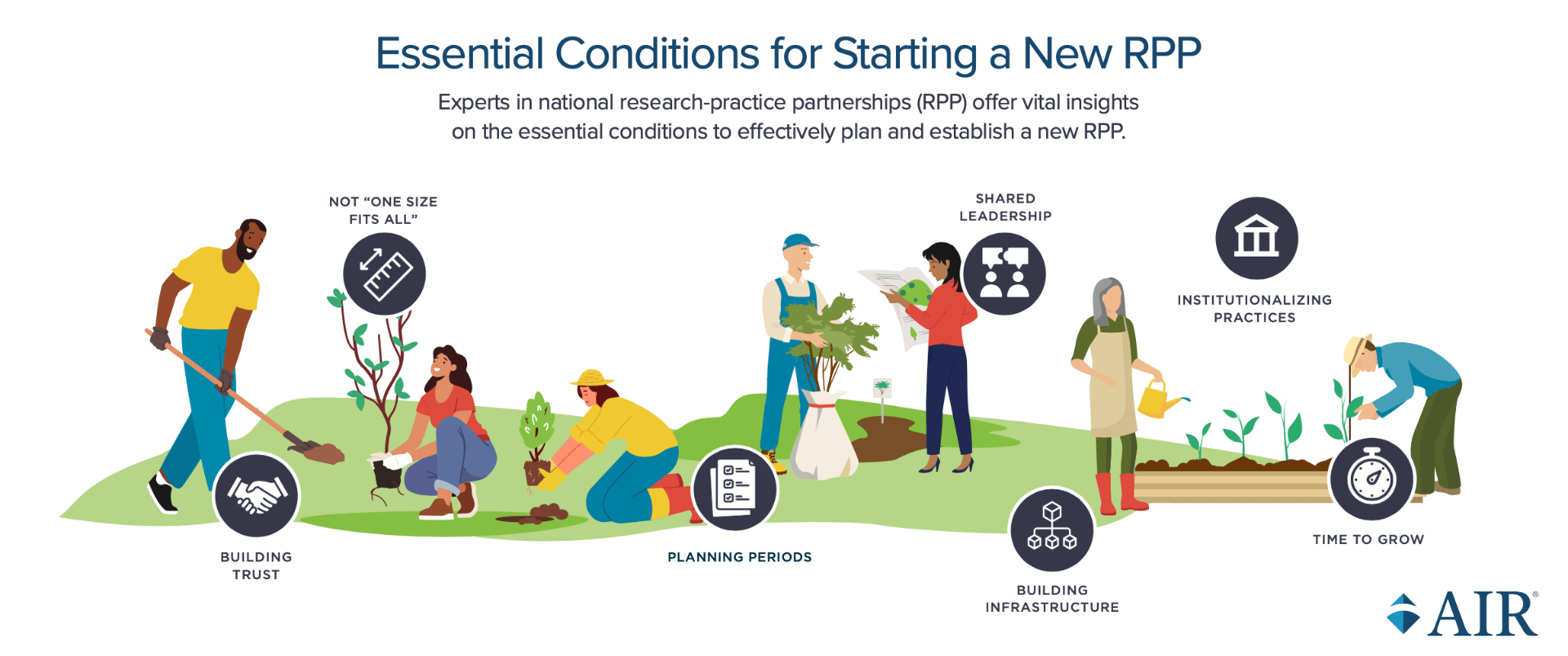

SEVEN THINGS TO KNOW ABOUT STARTING (AND MAINTAINING) AN RPP

I. Building trust is the essential foundation for creating RPPs. Trust, plus the efforts needed to develop and cultivate trust, were cited as the most important facets of developing a successful RPP by our group of RPP leaders. These efforts included building trust in formal and informal interactions and investing time in relationship development. This finding is consistent with the research literature on RPPs, which continually identifies trust as a nonnegotiable component (see, for example, Denner et al., 2019; Farrell et al., 2019; Henrick et al., 2017; Kochanek & Scholz, 2020). When interviewees shared their perspectives on “successful models” of RPPs, their examples primarily centered on developing a strong degree of trust between RPP participants or highlighted practices requiring trust as a precondition for success, such as collaboration, mutual ownership, shared decision making, and sharing formative ideas and findings with all partners for feedback and input.

II. RPPs must be designed in response to the needs and contexts of practitioners. Partnerships can be organized in many ways, and the design and approach for the RPP depends on the local context, needs, and goals of the participants. This finding is also consistent with emerging literature from the field (Farrell et al., 2022). As the number of RPPs expands, the field sees that having a specific “model,” such as place-based research alliances or a network improvement community (Coburn et al., 2013), is less critical than forming it to meet the goals and needs of members of the RPP. Despite the variation in how RPPs may be designed, there were common elements that participants named as important for any RPP, no matter the structure.

Table 1. Common important elements of RPPs, regardless of RPP model / structure

| The leadership structure should include leaders from the practice-side and the research-side as equal contributing members. |

| The mission, vision, and charter should be jointly developed and revisited across time to ensure that the RPP is meeting its explicit goals. |

| The research agenda should inform the research activities of the RPP and communicate priorities to diverse stakeholders. |

| Infrastructure, such as governance expectations, communication and dissemination plans, and funding (both for projects and operations), should help establish systems that enable the RPP to function. |

| Partnership members should be valued for their expertise, with practice-side and research-side partners contributing to shared leadership. Historical power imbalances should be considered and addressed within the relationship dynamics, and inclusivity should be the aim. |

III. Institutionalizing partnership practices is necessary to establish and maintain RPPs. Practices such as standing meetings, clear roles and responsibilities for all members of the RPP, and shared goals provide day-to-day stability and consistency for the RPP’s members. These routines provide a strong foundation for the RPP to realize its mission, vision, and charter and can intentionally hold the partnership accountable for engaging in mutually beneficial efforts. Although particularly important to establish at the inception of the RPP, these practices also continue to play valuable roles throughout the life of the RPP. Indeed, many interviewees noted that institutionalizing these practices helped them navigate periods of uncertainty, such as leadership changes and shifts in RPP goals and priorities.

IV. RPPs need to invest in infrastructure. Even though research is a leading activity of RPPs (Farrell et al., 2022), our interviewees noted that for research to occur and be successful, RPP infrastructure is critical. Specifically, the interviewees shared that establishing longer term systems and processes for data use agreements and research project approvals are critical to enable research efforts to occur. Interviewees also noted the importance of investing time to collaborate on communication and dissemination plans to ensure that the activities and outcomes of RPPs are accessible to multiple audiences and to demonstrate the contributions of the RPP. Research-side partners noted the importance of having multiple and diverse types of funding to support both research activities as well as RPP infrastructure.

V. To be successful, RPPs need committed partners and leaders from both sides of the partnership who can invest time in running the RPP and who have the authority to execute decisions. Interviewees noted that certain characteristics and leadership styles benefit an RPP, including curiosity, humility, and a genuine commitment to partnering and achieving shared goals through the RPP approach. They also named advisory boards as an important avenue for both diversifying perspectives for the RPP leadership team to consider and investing additional champions for the work of the RPP.

VI. New RPPs can benefit from planning periods, which could be as long as a year or two. The planning period is a time to establish shared agreement and consensus about the mission, vision, and goals of the RPP and to establish the foundations of how its leaders and members will work together. Interviewees also suggested that although there is no “right model” for an RPP, newly established RPPs would benefit from talking with leaders from long-standing RPPs. This enables newer RPPs to capitalize on lessons learned and potentially avoid—or at least mitigate—common challenges that RPPs experience.

Table 2. Advice From Our Interviewees on Lessons Learned/”I wish I knew…”

| Challenge | Suggested actions |

| Building trust | - Establish—and follow—a “no surprises rule”, meaning that there is time for advanced review of reports and findings prior to public release. - Establish expectations at the beginning and manage expectations continuously so that partners do not get frustrated by the time required to complete a project. |

| Demonstrating the value of the RPP | - For early “proof points,” focus on a few quick wins that the RPP can do quickly at the beginning. This will demonstrate the value and benefit of the RPP. |

| Navigating staff turnover | - Mitigate instability by having connections and relationships with multiple individuals in each organization so that if staff leave, there are still contacts and partners who have been working together on the RPP’s efforts. |

| Supporting use of research evidence | - Answer the questions people care about. Include end users in all phases of the research to ensure those who are affected are vested. Conduct research with, not on, people. |

| Communicating with diverse audiences | - Develop multiple formats and products to reach different audiences. - Ensure that publications are accessible, are timely, and use clear language (no technical jargon). |

| Establishing data use agreements | - Recognize that the legal agreements (i.e., memoranda of understanding, data-sharing agreements) will take substantial time to finalize; start this early in the process. |

| Planning for sustainability | - Secure diverse funding streams to support project costs and general operating/infrastructure costs. |

VII. Finally, know that developing RPPs takes time. As noted earlier, for an RPP to develop and thrive, trust must be established. Building trust takes substantial time. It also takes time to develop the routines and processes on which the RPP will rely. Some interviewees described RPPs that grew organically from other projects and partnerships and strengthened across time to become more formalized RPPs. It is essential for members from the practice-side and the research-side to be fully engaged in the process of developing the RPP; neither side can build it independently.

RECOMMENDATIONS

With these essentials of starting an RPP in mind, as shared by our group of RPP leaders, how might we prioritize these? Based on what we learned, newly forming RPPs should begin with efforts to develop a strong foundation and focus on building consensus among the participants within the RPP. Following that foundational stage, the next step should be a planning year (or years) for the RPP leaders and members to coalesce around the leadership structure; the operating structure and institutionalizing practices; the mission, vision, and charter; and the development of multiple funding streams. During the launch phase, RPP leaders and members could then focus on establishing the broader advisory and governance structures, building capacity for the partnership, ensuring the inclusion of diverse experiences and perspectives in the partnership, setting the initial research agenda, and developing and refining communication and dissemination plans.

Table 3. Phases of starting an RPP and activities to prioritize during each one

| Foundational | Planning Year(s) | Launch |

| Building consensus on the goals and aims of the RPP | - Establishing the leadership structure - Establishing the operating structure - Co-designing the mission, vision, and charter - Securing initial funding | - Establishing governance - Building capacity for the partnership - Ensuring diversity of expertise - Setting the research agenda - Creating communication and dissemination plans |

The leaders of the RPP will need to be prepared for the amount of time and commitment required to develop the partnership. In addition to attending to these conditions, researchers and practitioners need to embrace the spirit of RPP work. This process includes acknowledging that individually they may not have all the skills, knowledge, and capacity to lead the RPP yet, but these can be developed together across time; members can lean into their curiosity, capacity to learn, and commitment to drive the RPP forward.

Kylie Klein and Nora Gannon-Slater are Senior Researchers at American Institutes for Research.

NOTES

[1] This article is based on research funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The findings and conclusions contained within are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect positions or policies of the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

REFERENCES

Coburn, C., Penuel, W. R., & Geil, K. E. (2013). Research-practice partnerships: A strategy for leveraging research for educational improvements in school districts. William T. Grant Foundation. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED568396

Denner, J., Bean, S., Campe, S., Martinez, J., & Torres, D. (2019). Negotiating trust, power, and culture in a research-practice partnership. AERA Open, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419858635

Farrell, C. C., Harrison, C., & Coburn, C. E. (2019). “What the hell is this, and who the hell are you?” Role and identity negotiation in research-practice partnerships. AERA Open, 5(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/2332858419849595

Farrell, C. C., Penuel, W. R., Allen, A., Anderson, E. R., Bohannon, A. X., Coburn, C. E., & Brown, S. L. (2022). Learning at the boundaries of research and practice: A framework for understanding research-practice partnerships. Educational Researcher, 51(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X211069073

Henrick, E. C., Cobb, P., Penuel, W. R., Jackson, K., & Clark, T. (2017). Assessing research–practice partnerships: Five dimensions of effectiveness. William T. Grant Foundation. https://rpp.wtgrantfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/Assessing-Research-Practice-Partnerships.pdf

Kochanek, J., & Scholz, C. (2020). An exploratory study of how to use research-practice partnerships to build trust and support the use of early warning indicators. In L. Wentworth & J. Nagoka (Eds.) Early warning indicators in education: Innovations, uses, and optimal conditions for effectiveness. Teachers College Record Yearbook.

Kochanek, J. R., Scholz, C., Monahan, B., & Pardo, M. (2020). An Exploratory Study of how to Use RPPs to Build Trust and Support the Use of Early Warning Systems. Teachers College Record, 122(14), 1-28.

Suggested citation: Klein, K. & Gannon-Slater, N. (2023). What You Really Need To Know About Starting An RPP. NNERPP Extra, 5(2), 21-27. https://doi.org/10.25613/4TGZ-AS87