THE PROMISE OF A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH TO PROBLEM-SOLVING AND INNOVATION-TESTING: REFLECTIONS FROM A NEW RPP IN NEW YORK CITY

MDRC, a nonprofit social policy research organization, and the Office of Student Enrollment at New York City’s Department of Education (NYC DOE), are currently building a research-practice partnership (RPP) to address issues of educational equity in school application and enrollment. Called the Lab for Equity and Engagement in School Enrollment (E3 Lab), the partnership focuses on using insights from behavioral science and human-centered design to co-develop and test solutions that address operational challenges faced by the NYC DOE in efficiently ensuring equity and engagement in application and enrollment procedures. The work of the Lab builds on a long history of MDRC collaborations with NYC DOE (see for example, Hsueh, Corrin and Steimle, forthcoming[i]).

In this article, we consider the ways in which the problem-solving approach we are using to structure the activities of the Lab aligns with Henrick and colleagues’ five dimensions of effectiveness for RPPs and what it suggests about potential new indicators to measure progress on innovation and solution design.

The E3 Lab began as a research-practice project called Improving Engagement in Elementary School Selection. Initially designed to address barriers that families face with the kindergarten application process, the project was motivated by NYC DOE’s particular interest in focusing on barriers to application faced by families living in temporary housing and families for whom English is not a home language. The researchers (MDRC) and practitioners (Office of Student Enrollment at NYC DOE) came together as a team to complete a cycle of problem identification, solution design, and rigorous testing. The partnership allowed for mutual learning, where the researchers gained more practical knowledge and the practitioners were introduced to new evidence-based strategies. Setting an upfront goal of testing was critical to this work and its transformation into a longer partnership, because it supported a focus on building and using evidence in a concrete process that repeats each year—school application and enrollment.[ii]

Building on this initial project, MDRC and NYC DOE began collaboration on additional solution design, applying insights from behavioral science to other issues. Most recently, the team is working through rapid and iterative design cycles to pilot new messaging to families regarding changes in the school registration process related to COVID-19 school disruptions.

The E3 Lab features collaboration structures aligned to Dimension 1 of Henrick et al.’s framework—building trust and cultivating partnership relationships—that we hope will sustain and expand the RPP’s utility and efficiency over time. The structures include: i) Creating processes for NYC DOE and MDRC to jointly identify problems that map to areas of greatest interest for NYC DOE to ensure buy-in throughout the project lifecycle and sustainability beyond individual team members’ tenure, ii) designating a key contact at NYC DOE as a Co-Principal Investigator of individual projects, iii) collaborating on the development of all analysis plans to ensure analysis can be completed with available data (MDRC independently conducts impact analyses to evaluate interventions), iv) collaborating early in the intervention design process to build mutual capacity, allowing the researchers to share and apply evidence-based insights and the practitioners to apply critical practical knowledge, and vi) having researchers and practitioners co-present the project at local and national meetings and conferences.

Table 1: The Five Dimensions of Effectiveness from the Henrick, et al. Framework

| Dimension 1 | Building trust and cultivating partnership relationships |

| Dimension 2 | Conducting rigorous research to inform action |

| Dimension 3 | Supporting the partner practice organization in achieving its goals |

| Dimension 4 | Producing knowledge that can inform educational improvement efforts more broadly |

| Dimension 5 | Building the capacity of participating researchers, practitioners, practice organizations, and research organizations to engage in partnership work |

The initial project and now the E3 Lab are using MDRC’s Center for Applied Behavioral Science’s (CABS) six-step approach to problem-solving.

| The CABS Approach is a systematic problem-solving framework that MDRC has used in collaboration with 100 government agencies, educational institutions, and nonprofits in 26 states to uncover barriers, design creative solutions, and evaluate those solutions using rigorous research methods. At its core, the CABS Approach leverages principles of human-centered design and evidence from behavioral science to solve for key problems following six steps that may be sequential or cyclical: Define – Clarify – Diagnose – Design – Develop – Test. |

>> Step One: Define. The goal of the Define step is to clearly identify the problem affecting the population of interest that the project aims to solve. This first step ends with the creation of a neutral and measurable problem statement that can anchor the subsequent investigation into the causes of that problem and the design of solutions. Aligned with Dimension 3, it is essential that a problem statement be focused on a meaningful outcome that supports the practitioner organization’s goals. The Define phase of work also supports Dimension 1 by establishing a foundation of communication and work routines between the research and practitioner partners to carry through the remaining project phases.

To help the researchers better understand the practitioners’ goals and operational constraints, we brought together multiple district stakeholders (e.g. Office of Student Enrollment program and communications teams and staff from NYC DOE’s Research, Policy and Strategy Group) for this phase of work on the project. Our team co-created the following problem statement: “Many kindergarten-eligible families do not submit a kindergarten application by the January deadline.”

>> Step Two: Clarify. After we identify a problem statement, we clarify its context and scope using both qualitative and quantitative data sources. The descriptive research activities that anchor the Clarify step of the CABS Approach align with Dimensions 2 and 4 of the framework.

For the project, the team’s first task in the Clarify step was to develop a process map that visually represents all steps a family should take to successfully engage in the kindergarten application and enrollment process in NYC DOE. Next, the researchers observed and interviewed kindergarten-eligible families and NYC DOE staff who oversee and administer the kindergarten application and enrollment process to identify barriers families may face. The data collection and analysis from these events not only helped the team clarify the process and illuminate barriers, but also allowed the researchers to provide rapid feedback for the practitioners to inform time-sensitive decisions. For example, the researchers observed barriers to participation at information sessions hosted in family shelters and shared lessons from behavioral science about ways to improve outreach strategies. The practitioners rapidly applied some of those strategies in subsequent events by adjusting their promotional materials (e.g., fliers and letters) to align with best practices from behavioral science.

In addition to the qualitative analysis, the researchers also conducted quantitative analysis as part of the Clarify step to identify where in the process families were dropping out or disengaging. Specifically, the researchers analyzed early childhood and kindergarten application and enrollment pathways of a prior cohort of students constructing data visualizations to show the relationship between pre-kindergarten and kindergarten application and enrollment behaviors. This analysis helped the RPP team refine the problem statement by clarifying its scope: “Among kindergarten enrollees in the 2016-2017 school-year 28% fell into the application gap, meaning they did not participate in the application process.” This analysis approach also built conceptual capacity for the practitioners by demonstrating new ways for them to examine their data and highlighting new populations in need of targeting. Consistent with Dimension 4, the researchers published a brief on the findings to contribute to research literature on challenges families face in school application processes.[iii]

Understanding and framing the problem as an “application gap”—people who potentially could apply but do not, despite ultimately enrolling —allowed the RPP team to highlight to district leadership and to other researchers why this problem was meaningful and had equity implications. Specifically, families falling into the “application gap” miss out on opportunities to fully exercise school choice for kindergarten since high-demand schools can fill up during the application period. The families may also miss out on opportunities to connect with the school and engage in kindergarten activities before the school year begins. The gap is also meaningful for the districts and for schools because it creates uncertainty in planning activities due to fluctuating rosters during the summer and early fall. The fact that our analysis found that English Language Learners and children living in temporary housing were over-represented in the application gap further bolstered motivation from the RPP team and important stakeholders to address this challenge.

>> Step Three: Diagnose. During the Diagnose step, the team uses the qualitative and quantitative data collected during the Clarify step to identify barriers that may be causing the problem. The team then draws on behavioral science research to develop hypotheses about the behavioral reasons for the barriers, or drop-off points, in the process map that was jointly created.

For the project, our team leveraged the original data, insights from behavioral science, and prior research literature on school choice to co-create hypotheses about the barriers that families face in the NYC kindergarten admissions process. This insight generation process aligns with Dimension 4 of the framework as it can suggest additional hypotheses that can be explored empirically in other settings. The Diagnosis step is also integral to the development of innovative context-specific solutions informed by behavioral science.

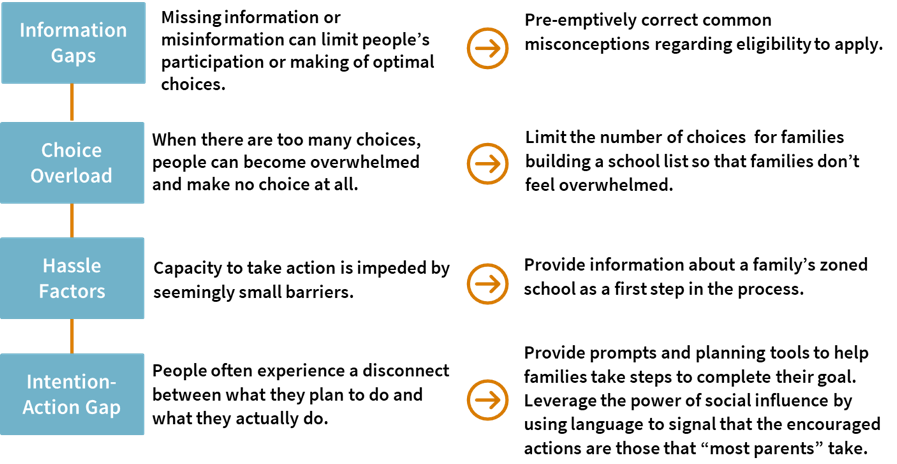

In alignment with NYC DOE’s priorities for the project, our team focused particular attention on barriers faced by families living in shelters and those for whom English is not a home language. For example, we found that some families were overwhelmed by the prospect of indicating twelve schools on their application and were not familiar with schools available in the neighborhood where their shelter was located. We know from behavioral science research and the prior literature on school selection that barriers such as information gaps and choice overload can impede action.[iv]

>> Step Four: Design. In the Design step, the team develops solutions to address the barriers uncovered during Diagnosis. The district’s operations, infrastructure, and preferences for certain formats (e.g., paper vs. digital application; privacy rules about who can be reached, how, and when; deadlines that cannot be changed because of staff commitments to other grades’ application timelines) created parameters for our joint design process.

Exhibit 1: Behavioral Barriers and Solutions from the E3 Lab’s Digital Intervention (Kindergarten Application Helper)

For the project, our team drew on CABS tools for designing solutions (see SIMPLER framework and communications checklist) and prior school choice interventions[v], but recognized that this intervention would be less about improving choice and more about easing application. Thus the team co-designed a digital intervention intended to address barriers that families face in the NYC DOE kindergarten application process—an online “Kindergarten Application Helper” (called “K Helper”) that simplified decision making, and included an opt-in text message campaign offering reminders about the application timeline. In all discussions with the practitioners about the intervention design ideas, the researchers highlighted the specific barriers being targeted and behavioral principles underlying the solution ideas. In alignment with Dimension 5, NYC DOE has independently applied many of the design features of the RPP team’s intervention to other projects outside of the partnership. For example, after implementation of the “Kindergarten Application Helper” for the RPP project, NYC DOE developed a similar feature in their broader application system to support parents’ identification of early childhood programs for which they have highest priority to attend, incorporating a set of questions and search tools from the K Helper. This activity demonstrates that the partnership supported the practitioner staff’s capacity to apply principles of behavioral science on their own.

>> Step Five: Develop. The Develop step focuses on ensuring the proposed solutions are feasible to implement and sustain, if found to be effective, and can be used by the target populations as intended. To this end, the team gathers feedback from stakeholders and uses that feedback to iterate and improve upon the solution. Since the practice organization often must carry the burden of implementation of the solution at scale, the Develop step requires the team pay careful attention to buy-in from the practice organization as well as feasibility and usability of the solution when implemented at scale. Finally, in alignment with Dimensions 2 and 4, the research team needs to take care during the Develop step to clearly communicate implications of intervention design decisions for the research questions that can be asked and answered in the subsequent testing phase, and the appropriate research design that can answer those questions and be implemented well. Sometimes, priorities will need to be set, and tradeoffs made.

Our experience in the Develop step of the project demonstrates the importance of attending to Dimension 1 in this critical time of problem-solving and testing. Our RPP team initially wanted to focus implementation and testing of the “K Helper” solutions for those families that the quantitative analysis suggested were most at-risk of falling into the application gap for kindergarten (e.g. previous non-applicants to pre-kindergarten). However, based on early feedback from the practitioner partner organization, our team learned that for a number of operational reasons, it would not be feasible to target outreach to previous pre-kindergarten non-appliers. As a result, we decided that it would be best to start implementation with families for whom the practitioners already had routines for digital outreach (subscribers to NYC DOE Office of Student Enrollment digital updates and prior pre-kindergarten applicants) and would be receiving standard NYC DOE notifications in the absence of the intervention. With this change in the target population for the implementation of the intervention, the research team had to adjust elements of the theory of change for the intervention and associated analysis plans before pre-registering the plan at the Registry of Educational Effectiveness Studies (REES).

Although this decision to shift the target population meant that the study was less targeted and the intervention potentially less impactful, the experience reflects the progress that the RPP has made on Dimension 1. It was the strong communication structures and tight relationships between the research and practitioner team members of the RPP that enabled this issue to be raised early enough for a change to be made early in the research plans and for the RPP team to identify an alternate path that would still meet the objectives of the practice organization to implement and test the efficacy of the solutions.

>> Step Six: Test. The Test step is the final phase of the CABS Approach when the team deploys and monitors the implementation of the new solutions and evaluates them to determine effectiveness. In the Test step, the research partner not only measures effectiveness of the intervention at achieving the intended outcomes but also documents the experience of the practitioners implementing the solutions including facilitators and barriers. Consistent with MDRC’s mission, the Test step includes dissemination of findings to practitioners and policymakers. The Test step aligns with Dimensions 3 and 4 by building rigorous evidence about the efficacy of solutions for the partner practice organization and the broader field.

For the project, the team randomly assigned potential kindergarten applicants (subscribers to NYC DOE email updates and former pre-kindergarten applicants) to receive NYC DOE’s standard email notifications about the kindergarten admissions process or the RPP team’s email that included behavioral messaging encouraging families to visit the “Kindergarten Application Helper” webtool where they could also sign up for text message reminders about the application process. The researchers are now independently conducting the impact analysis that will be shared with NYC DOE and then the broader field.

School districts can find themselves grappling with equity challenges in many areas of their operations, and may look to researchers to go beyond pointing out disparities and help them design, pilot, test, and scale potential solutions. As decades of research on education reforms and interventions have shown us, designing solutions for challenges rooted in pervasive and persistent inequalities is very difficult work. Getting to solutions will require significant innovation from researchers and practitioners. RPPs that align with Henrick and colleagues’ dimensions of effectiveness are uniquely situated to take on this challenge. Based on our reflections on how our approach in the E3 Lab aligns to the Framework, we are hopeful that our growing partnership will help achieve its lofty goals of improving equity in families’ experiences with NYC DOE school enrollment. As we consider successes and challenges of our first project of the E3 Lab, we wonder if the RPP community might consider expanding the Framework to include new indicators that focus on structures and routines to support innovation via strong problem identification, solution design, and testing. Using a systematic framework for collaborative problem identification, intervention design, and testing (like the CABS Approach) is one way that RPPs can infuse mutual learning via innovation into their approach. Extending this collaboration to a joint approach to testing can help advance evidence building and evidence use.[vi]

Barbara Condliffe is Research Associate, K-12 Education Policy Area and Center for Applied Behavioral Science, at MDRC, Rekha Balu is Senior Fellow and Director, Center for Applied Behavioral Science, and Margaret Hennessy is also a Research Analyst, K-12 Education Policy Area. Rachel Leopold is the Director of Enrollment Research & Policy at the New York City Department of Education Office of Student Enrollment.

[i] Hsueh, J., Corrin, W., & Steimle, S. Forthcoming. “Building Towards Effectiveness: How MDRC Supports Continuous Learning, Evidence-Building, Implementation, and Adaptation of Programming at Scale.” New York: MDRC.

[ii] Balu, R., Dechausay, N., & Anzelone, C. (2019). Organizational Approach and Processes for Applying Behavioral Insights to Policy. Behavioral Insights in Public Policy: Concepts and Cases. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

Bangser, M. (2014). A Funder’s Guide to Using Evidence of Program Effectiveness in Scale-Up Decisions. New York, NY: MDRC. Retrieved from: https://www.mdrc.org/sites/default/files/GPN_FR.pdf

[iii] Bell, C. A. (2009). All choices created equal? The role of choice sets in the selection of schools. Peabody Journal of Education, 84(2), 191–208.

Condliffe, B. F., Boyd, M. L., & DeLuca, S. (2015). Stuck in school: How social context shapes school choice for inner-city students. Teachers College Record, 117(3), 1–36.

DeArmond, M., Jochim, A., & Lake, R. (2014). Making School Choice Work. Center on Reinventing Public Education. Retrieved from: https://www.crpe.org/sites/default/files/CRPE_MakingSchoolChoiceWork_Report.pdf

Fong, K. (2019). Subject to evaluation: How parents assess and mobilize information from social networks in school choice. Sociological Forum, 34(1), 158–180.

Fong, K., & Faude, S. (2018). Timing Is Everything: Late Registration and Stratified Access to School Choice. Sociology of Education, 91(3), 242–262.

Mavrogordato, M., & Stein, M. (2016). Accessing choice: A mixed-methods examination of how Latino parents engage in the educational marketplace. Urban Education, 51(9), 1031–1064.

Neild, R. (2005). Parent Management of School Choice in a Large Urban District. Urban Education, 40 (3), 270-297.

Rhodes, A., & DeLuca, S. (2014). Residential mobility and school choice among poor families. In Lareau, A. and Goyette, K. (Eds.), Choosing Homes, Choosing Schools, (pp. 137-166). Russell Sage Foundation.

Sattin-Bajaj, C. (2015). Unaccompanied minors: How children of Latin American immigrants negotiate high school choice. American Journal of Education, 121(3), 381–415.

[iv] Chernev, A., Böckenholt, U., & Goodman, J. (2015). Choice overload: A conceptual review and meta-analysis. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 25(2), 333-358.

Glazerman, S., Nichols-Barrer, I., Valant, J., Chandler, J., & Burnett, A. (2018). Nudging Parents to Choose Better Schools: The Importance of School Choice Architecture. (Mathematica Working Paper Series, No. 65). Princeton, NJ: Mathematica Policy Research.

Hadar, L., & Sood, S. (2014). When knowledge is demotivating: Subjective knowledge and choice overload. Psychological Science, 25(9), 1739-1747.

[v] Corcoran, S.P., Jennings, J.L., Cohodes, S. R., and Sattin-Bajaj, C. (2018). Leveling the Playing Field for High School Choice: Results from a Field Experiment of Informational Interventions. NBER Working Paper Series, No. 24471. Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

Hastings, J. S., & Weinstein, J. M. (2008). Information, school choice, and academic achievement: Evidence from two experiments. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(4), 1373–1414.

Weixler, L., Valant, J., Bassok, D., Doromal, J., and Gerry, A. (2018). Helping Parents Navigate the Early Childhood Enrollment Process: Experimental Evidence from New Orleans. Education Research Alliance for New Orleans. Retrieved from: https://educationresearchalliancenola.org/files/publications/Weixler-et-al-ECE-RCT-6_7.pdf

[vi] Tseng, V. & Coburn, C. (2019). Using Evidence in the U.S. from What Works Now: Evidence-informed Policy and Practice. New York, NY: William T. Grant Foundation. Retrieved from: http://wtgrantfoundation.org/library/uploads/2019/09/Tseng-and-Coburn-_What-Works-Now.pdf

Cody, S., & Arbour, M. (2019). Rapid Learning: Methods to Examine and Improve Social Programs. (OPRE Report #2019-86.) Washington D.C.: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Suggested citation: Condliffe, B., Balu, R., Hennessy, M., & Leopold, R. (2020). The Promise of a Collaborative Approach to Problem-Solving and Innovation-Testing: Reflections from a New Research-Practice Partnership in New York City. NNERPP Extra, 2(2), 14-18. https://doi.org/10.25613/72WX-YC16