USING APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY TO STRENGTHEN RPPs

Research-Practice Partnerships (RPPs) offer a model for mutually beneficial learning and capacity building across disciplines and contexts. Bringing together professionals with different skills and areas of expertise can foster innovation with the goal of creating equitable transformation and improvement. Within these partnerships, individuals often need to approach the work with a different set of skills and mindsets than they might otherwise draw from in their regular roles as researchers, teachers, administrators, or policymakers. Several resources have examined the kind of personal capacities needed for working collaboratively across disciplines and considered the complex ways in which context, systems, and structures external to and within our partnerships shape the work, such as the 2023 Towards a Field for Collaborative Education Research: Developing a Framework for the Complexity of Necessary Learning framework and the 2022 Brokering in Education RPPs Handbook. Frameworks such as these can be incredibly helpful in supporting RPP participants in understanding, assessing, promoting, and furthering their partnership work.

Our RPP team at WashU’s Institute for School Partnership (ISP) has looked to various approaches and practical tools to help us navigate the complexities of partnership work. Appreciative Inquiry is one such approach that has proved valuable to us, and we think it can be helpful to other RPPs as well. To that end, this article examines Appreciative Inquiry as an approach to surface, understand, and provide solutions in RPPs. In particular, we share how our partnership has used Appreciative Inquiry in supporting improvement science projects, in strengthening professional learning activities, and in evaluating the health of our partnership.

A QUICK LOOK AT OUR RPP

The Institute for School Partnership began as an informal partnership between a biology professor and her children’s school, first formalized in 1990. Now, the ISP partners with over 5,000 educators in hundreds of schools annually, primarily in the St. Louis, Missouri region, to bridge the gap between research and practice in education through co-designed solutions that create equitable, supportive conditions for learning. The ISP’s work falls into three main buckets: facilitating partnerships between STEM faculty and teachers to translate scientific research to the classroom (e.g., summer teacher researchers); improvement and professional learning partnerships to translate education research into school contexts (e.g., math instructional improvement); and, curricular design and infrastructure to build systems that support practitioner use of research evidence (e.g., mySci curricular program). Our team works across an array of projects with multiple functions, including: as brokers of both research evidence and partnerships between researchers and educators; as hubs facilitating knowledge sharing and improvement testing; and, as a resource to educators in the field providing professional learning and curricular resources. The ISP uses a braided funding model to allow for flexible, sustainable relationships with schools and teachers; this combination of grants and fee-for-service funding supports interconnected professional learning, curriculum design, and research activities.

AN INTRODUCTION TO APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY

Appreciative Inquiry has its roots in health care organizational behavior research as a change philosophy that formalizes a strengths-based approach into a model that can support organizational function and improvement. The approach centers on identifying existing successes within a group or organization and building upon these to enhance overall performance.

Appreciative Inquiry is built on several basic assumptions about human psychology and group dynamics; chief among these is that in “every society, organization, or group, something works” (Hammond, 2013, p. 14). While the foundational goal of many RPPs is to solve a problem of practice, Appreciative Inquiry suggests that by starting from the assets and past successes, we can learn from and apply the circumstances and factors of those successes to less successful areas.

The eight Assumptions of Appreciative Inquiry are (Hammond, 2013):

- In every society, organization, or group something works.

- What we focus on becomes our reality.

- Reality is created in the moment, and there are multiple realities.

- The act of asking questions of an organization or group influences the group in some way.

- People have more confidence and comfort to journey to the future (the unknown) when they carry forward parts of the past (the known).

- If we carry parts of the past forward, they should be what is best about the past.

- It is important to value differences.

- The language we use creates our reality.

From these assumptions, the Appreciative Inquiry “5D Process” provides a step-by-step approach to change (Hammond, 2013):

- Definition: What is the focus of the inquiry?

- Discovery: Appreciating the best of “what is”

- Dream: Envisioning “what could be”

- Design: Create shared images of a “what could be”

- Destiny/Deliver: Create & sustain “what will be”

In Appreciative Inquiry, the Definition phase sets the scope for the work by defining and refining the topic of inquiry and focus. During the Discovery phase, Appreciative Inquiry calls upon participants to “appreciate the best of ‘what is’” through appreciative interviews which are a main driver of the 5D Process. Participants interview each other and/or stakeholders across their organizations with appreciative focused questions. Through these interviews, participants search for the underlying causes of success at the personal, interpersonal, and systems levels. During the Dream phase, participants share the results of their interviews and look for common themes. The outcome of these conversations is an articulation of key strengths and sets the stage for setting a shared vision of success for the team to use as a basis of their Design phase. The last phase of Appreciative Inquiry is alternately called the Destiny or Deliver phase, during which participants put their plans into action.

At the ISP, we have drawn from Appreciative Inquiry in various ways across our RPP work: to facilitate school improvement projects led by teachers and administrators; as a learning tool in professional development; and as an evaluation tool to collect data and better understand the strengths of our partnership.

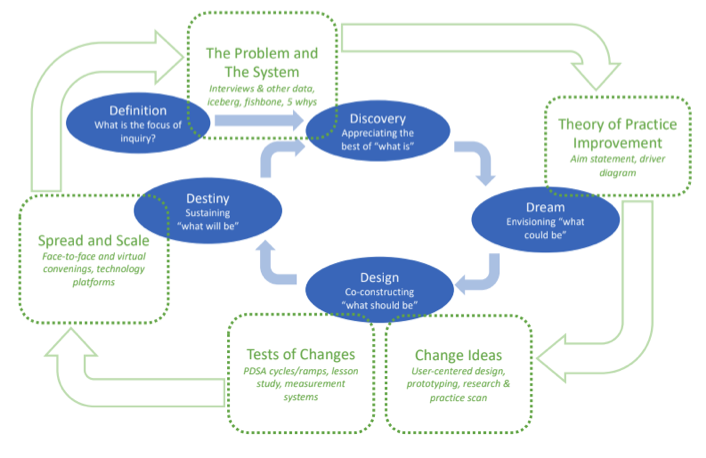

(I) APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY AND IMPROVEMENT SCIENCE

One of the powerful applications of Appreciative Inquiry in our work has been in facilitating school improvement projects led by teachers and administrators in a networked improvement community (NIC). NICs are learning communities built to accelerate testing and diffusion of solutions to a common problem using the principles and tools of improvement science. This NIC included multiple school districts with a common desire to implement and support equitable math instruction. The ISP had a history of individual collaboration with each district partner and sought to leverage their strengths in the NIC’s learning. From the start, participants in the NIC, including ISP researchers, data analysts, and professional learning facilitators as well as teacher leaders and administrators, felt uncomfortable with the “problem focus” of improvement science. Together, the members of the RPP developed a framework for continuous improvement drawing from both improvement science (Bryk et al., 2015) and Appreciative Inquiry (Figure 1) (Trager & Ruggirello, 2022). This framework allowed us to shift our thinking from “problems we need to solve” to “finding and spreading what works.” While semantic, this shift was not trivial. As our NIC dove into iterations on instructional improvements, we found that the tools and mindsets of Appreciative Inquiry interrupted the natural impulse to find fault or blame and helped motivate participants to persevere, seeing “failed tests” as part of the design process.

Figure 1. A Framework for Continuous Improvement, Trager & Ruggirello, 2022

In this hybridized approach, the ISP team trained the NIC participants on Appreciative Inquiry principles and techniques. Together, researchers, professional development providers, administrators, and teachers in the NIC completed appreciative interviews of each other and of their colleagues and students in their schools. Through these interviews, we quickly unearthed valuable insights and drove the development of the NIC’s motivational aim statement and theory of improvement.

By using the language of “dreaming” we challenged ourselves to think outside the box of our founding charge around building instructional capacity to how we could build buy-in for changes across systems and create opportunities for teacher leadership and growth. These “dreams” became key “designs” of the NIC’s driver diagram. Throughout the NIC, the team also used appreciative interviewing as a data collection tool during Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) cycles (e.g. asking students what helped them better understand a concept during the lesson).

The NIC returned to appreciative interviews multiple times as a way to reinforce positive relationships across contexts, build buy-in with decision makers, and to celebrate achievements motivating team members. In one case, survey data pointed to an issue with the curricular materials used in two of the three participating districts. In addressing this data together, participants reframed the conversation from an appreciative lens celebrating the positive role that high-quality instructional materials had played in instructional successes, thus smoothing any ruffled feathers and creating a more palatable argument to make off-cycle curricular changes.

(II) APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY IN PROFESSIONAL LEARNING

The successes we experienced in using Appreciative Inquiry in the NIC spilled over into other ISP RPP activities. Instead of applying the whole Appreciative Inquiry 5D Process, we have drawn from the assumptions and used tools from the approach independently. The appreciative interview has been a particularly powerful tool for connecting with educators and helping them better connect with each other to learn. In professional learning with educators across a variety of contexts, we often ask participants to pair up and conduct brief appreciative interviews with each other, reporting back to the group to reflect and set intentions for their learning.

Here are some appreciative interview questions we have used in professional learning activities facilitated by our RPP:

- Without being humble, what do you value most about yourself—as a person, as a learner, and as a change agent?

- Considering your entire time as a member of your school community, can you recall a time when you felt most alive, most involved, or most excited about your involvement in the school?

- What strategies have worked for you in capturing student thinking?

- In your mind, what is the common purpose that unites everyone in your school?

- What do you see as your role in bringing about equitable, engaging math education that prioritizes the inclusion of every student in your school?

We have found that asking teachers to interview each other and share their experiences has opened informal avenues to support deeper, more meaningful collaboration. In this context, educators can share strategies and resources with each other as well as with the larger group. The pairing off has also encouraged teachers to form informal networks of support and mentorship. Additionally, professional development facilitators have been able to refer back to appreciative interview findings to help teachers put together plans to use what they learned in their instruction.

In professional learning communities (PLCs), we have used appreciative interviews as a tool to support the teams in building group cohesion and buy-in around their purpose. We have also trained school administrators to conduct appreciative interviews as a tool to gather feedback and ideas with their staff and school community. Across our embedded professional learning work with our school partners, we can use this as a tool to support connection and introduce the language of dreaming and the idea of ‘destiny’ or collective vision to bring a culture of appreciation into our work, which reinforces positive and productive partnerships.

(III) APPRECIATIVE INQUIRY IN EVALUATION

Evaluation is crucial to RPP success, both in terms of the developmental and outcomes evaluation of the RPP’s work in different projects and the continuous assessment of the partnership itself. Evaluation of the processes and impacts of our RPP demonstrates the value of and allows us to better advocate for our work. Evaluation can also build the capacity and improve the effectiveness of the RPP itself, motivating participants and deepening the connections between the research and their practice.

Formal developmental and outcomes evaluation in the course of our RPP work is one of the ways that our team enacts the dimensions of RPP effectiveness, especially with regard to engaging in inclusive inquiry to address local needs (dimension 2) and in supporting partners in making progress toward their goals (dimension 3). We have found that incorporating Appreciative Inquiry into our RPP work produces relevant, analyzable artifacts of that work. For example, appreciative interview notes from our NIC participants’ interviews of each other not only allowed the group to develop an aim statement and supported the formation of the NIC’s theory of action, but also became data in an evaluation tracking changes in math instructional practices and vision over time as the group repeated the exercise multiple times over the course of the program. These artifacts also provide a rich data set that can be explored when we encounter novel findings, allowing us to better understand positive deviation in the data. These interviews produce a wealth of first hand accounts that can be especially compelling for private funders.

The ISP also functions as an RPP broker, bringing together and supporting external researchers and educators. In this role, we also work to strengthen the partnership through assessment and continuous improvement of that partnership, which is a key function of RPP brokers. Additionally, we have also often turned to Appreciative Inquiry as a basis of our ongoing assessments of the RPP. We start from the question “what is working in this partnership” and use that to guide our data collection and analysis. For example, in a project bringing together ecologists, elementary school teachers and students, and curricular design specialists, we were able to capitalize on strong personal relationships and engage parents from the school community in the RPP as professionals on the project. Leaning into the strength of those connections guided the RPP in answering questions regarding the allocation of resources and time, such as whether they should expand to include middle and high school students or to additional elementary schools – in this case, they chose to expand across elementary buildings to better leverage their experience with family engagement.

Starting from the partnership’s strengths has been key to building routines for reflection into our partnership meetings as well. When our conversations and questions center on our successes and we value the variations, it really does shape the reality and build consensus across partners. In practice, it is important to note that “centering our successes” should not be handled as a kind of toxic positivity, but rather a tool to address issues that arise or barriers that we encounter by focusing on what made the success different and how we can apply that to the current dilemma. This approach has been especially helpful in combating the effects of the sunk cost fallacy in supporting RPP partners' navigation of change over the course of the partnership. When you focus on “doing more of what works”, you are not losing anything which helps folks let go of the need to keep trying when something isn’t working. Framing and language have immense power to shift our mindsets.

IN CLOSING

In our RPP, we generally favor a bricolage approach, applying many different methodologies, frameworks, and theories, often in tandem with one another, to best fit the context or need at hand. The assumptions of Appreciative Inquiry provide a compelling set of principles that can be applied in many different ways. Using appreciative interviewing and ‘dreaming’ debriefs as tools across contexts –even contexts that might not have originally been intended for– has helped our team collaborate more meaningfully with schools and educators and in sharing those tools, we have helped them build healthier systems and connections.

In closing, we leave you with a few ponderings: Do the assumptions of Appreciative Inquiry resonate with you/make sense in your context? Are there ways you are using Appreciative Inquiry in your RPPs? How might you use the principles, processes, or tools of Appreciative Inquiry, in whole, independently, or in other contexts to support educational improvement and RPP initiatives?

Maia Elkana is Evaluation Director and Victoria May is Executive Director of the Institute for School Partnership at Washington University in St. Louis.

References

Bryk, A. S., Gomez, L. M., Grunow, A., & LeMahieu, P. G. (2015). Learning to improve: How America’s schools can get better at getting better. Harvard Education Press.

Hammond, S.A. (2013) The Thin Book of Appreciative Inquiry, 3rd ed. Bend, OR: Thin Book Publishing Co.

Trager, B. & Ruggirello, R. (2022). Using a Framework for Continuous Improvement to Catalyze Change in Middle School Mathematics. In K.J. Graham, R.Q. Berry III, S.B. Bush, & D. Huinker (Eds.), Success Stories from Catalyzing Change (pp. 53-60). National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Suggested citation: Elkana, M. & May, V. (2025). Using Appreciative Inquiry to Strengthen RPPs. NNERPP Extra, 7(3), 15-22. https://doi.org/10.25613/35H9-DM21