SEEING AND SUPPORTING ALL STUDENTS THROUGH STRONG TEACHER-STUDENT RELATIONSHIPS

OVERVIEW

The Research

Here, we highlight insights from research that was conducted over the course of the last three years around strengthening teachers’ capacity to engage with marginalized students to help them thrive. (We are currently prioritizing sharing findings directly with our district partners so public-facing publications are not available at this time; however, we are planning to publish more about our research through journal articles in the future.)

The RPP

Founded in 2018, the Northwestern-Evanston Education Research Alliance (NEERA) collaboratively leverages the expertise of researchers and practitioners in and out of school to promote the learning and development of the young people of Evanston and the world beyond. Partners include Northwestern University, Illinois Public School District #202 (Evanston Township High School), and Illinois Public School District #65 (Evanston-Skokie K-8).

Through the development of participatory learning communities, this ongoing research-practice partnership (RPP) partners researchers with educators at all levels of the educational system and positions teachers at the center of this work. In doing so NEERA aims to move beyond surface-level intervention and foster sustainable change in how students—particularly those from historically marginalized backgrounds—experience school.

WHY THIS WORK

Strong teacher-student relationships are central to students’ motivation, well-being, and academic success. Research consistently shows that when students feel supported by their teachers, they are more engaged in learning, better able to navigate challenges, and more likely to thrive both socio-emotionally and academically (Jennings & Greenberg, 2009; Jones & Kahn, 2017). Yet, research continuously finds that students from historically marginalized backgrounds often report feeling less supported and connected to their teachers, compared to their non-marginalized peers (Rivera-Rodriguez & Mercado, 2024). Humanizing pedagogies—education practices that center students’ unique backgrounds, identities and lived experiences within educational contexts—offer alternatives to traditional teaching frameworks that are especially effective in strengthening teachers’ relationships with students, especially those who are from historically marginalized backgrounds (Destin et al., 2022; see Table 1).

Table 1: Humanizing approaches differ from traditional pedagogy in four key ways.

| Traditional Pedagogy | Humanizing Pedagogy |

| Teacher-centered, top-down | Student-centered, relational |

| Focus on compliance and control | Focus on student agency & engagement |

| Abstract, standardized content | Contextualized, lived experiences |

| Knowledge as static & fixed | Knowledge as co-created by both teachers and students |

WHAT THE WORK EXAMINES

As research continues to show the positive impact of humanizing pedagogies on student outcomes, school districts across the country have invested in policies, initiatives, and teacher training programs intended to promote humanizing pedagogies with varying levels of success. Institutional constraints rooted in traditional approaches to education often make it challenging for teachers to translate research into practice (Sleeter, 2012; Cochran-Smith & Lytle, 2009). Promoting the cultural shifts necessary to overcome these rigid structures requires sustained effort, support, collaboration, and trust between educators and researchers.

In NEERA’s partner districts, supporting students from historically marginalized communities has emerged as a priority, and we as an RPP have embraced humanizing pedagogy as an approach to support teachers in doing so. Over the last three years, we have seen the humanizing pedagogy approach and the creation of teacher learning communities be an effective and powerful strategy to advance practitioner-centered, participatory research that can create cultural change. In this article, we share insights and research findings from those three years working with a middle school in one of our partner districts, starting from how this research priority first emerged and outlining what our work together has looked like since then.

WORK AND FINDINGS

(I) YEAR 1: Conversations with School Leadership

The NEERA partnership draws on the Cultural Change Cycle (CCC) framework (Brady et al., 2024) to support sustainable change within local K-12 education systems. Following this framework, the partnership began with collaborative discussions between district and university leaders to identify research priorities aligned with the district’s commitment to education equity. One core priority that emerged was strengthening teachers’ capacity to engage and support students from historically marginalized backgrounds. A research team was then assembled to work collaboratively with interested staff to explore strategies and share insights in support of this goal.

Through these conversations with staff, the research team—composed of faculty, post-docs, graduate students and undergrads—identified an opportunity to co-design a professional development workshop to promote humanizing pedagogies as an evidence-based strategy to strengthen teacher relationships with students from marginalized backgrounds. This workshop was developed in collaboration with teachers. Researchers shared psychological research on student identity and academic motivation while teachers shared institutional knowledge and personal experience to ensure the workshop was engaging for staff. The final design of the workshop aimed to challenge socially ingrained narratives that position students’ marginalized identities as deficits and barriers to academic success by promoting counterexamples of the beneficial skills and perspectives that students gain as a direct function of their marginalized identities. It also highlighted psychological research to show how teachers’ orientations towards strength-based versus deficit-based narratives ultimately influence student outcomes.

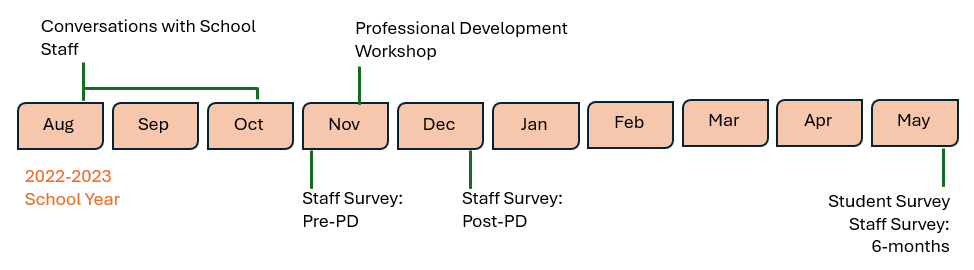

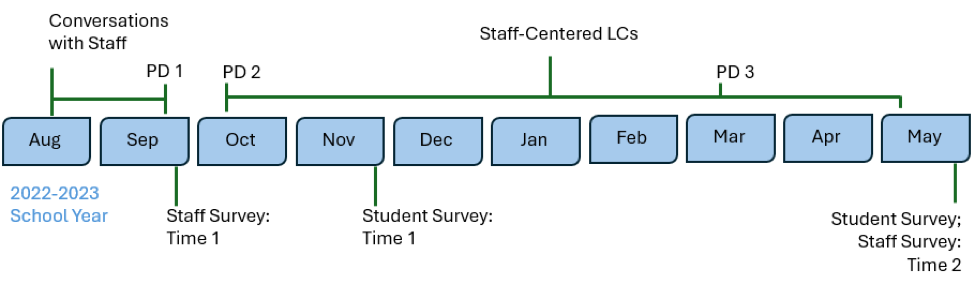

This workshop was administered to all staff members a few months into the school year. Staff were invited to participate in a longitudinal survey to examine the trajectory of teachers’ strength-based and deficit-based orientations towards students’ marginalized backgrounds following the workshop. The timeline of these research activities is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Timeline of research activities during the first year of this project.

Teacher and Student Outcomes

We collected survey data from teachers at three different timepoints to capture teachers’ orientations towards strength-based and deficit-based narratives about students’ marginalized identities following the workshop (see Figure 1). We also collected survey data from students at the end of the year to measure feelings of support. Additionally, district partners shared administrative data to examine whether students’ feelings of support were associated with academic outcomes (i.e., end-of-the-year grades).

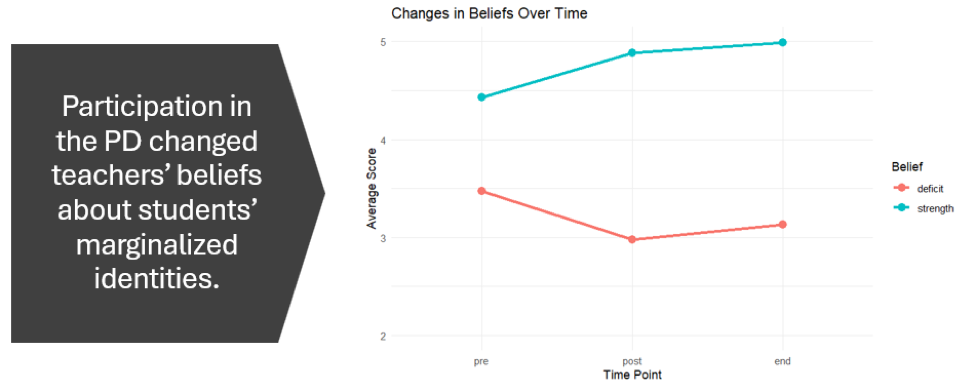

Results indicated a significant increase in teachers’ strength-based orientations and a significant decrease in deficit-based orientations after participating in the workshop (see Figure 2). In particular, participation in the workshop was associated with increases in teachers’ beliefs that students gain beneficial skills and perspectives as a direct function of their marginalized identities, and decreases in beliefs that marginalized identities are a barrier to student success.

Figure 2: Participation in the PD changed teachers’ beliefs about students' marginalized identities, with a significant increase in teachers’ strength-based orientations and a significant decrease in deficit-based orientations.

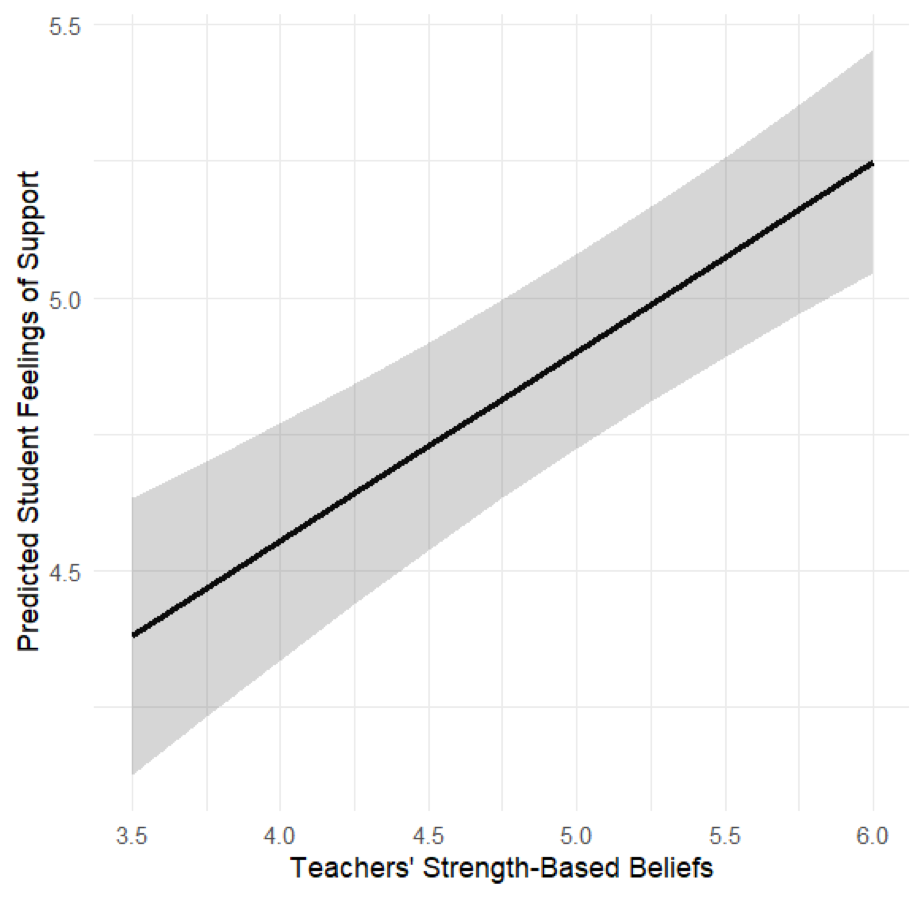

Teachers’ strength-based beliefs were further shown to predict students’ feelings of support, such that students felt more supported by teachers who hold strength-based orientations towards their students’ backgrounds (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Teachers’ strength-based orientations predict greater feelings of support among students.

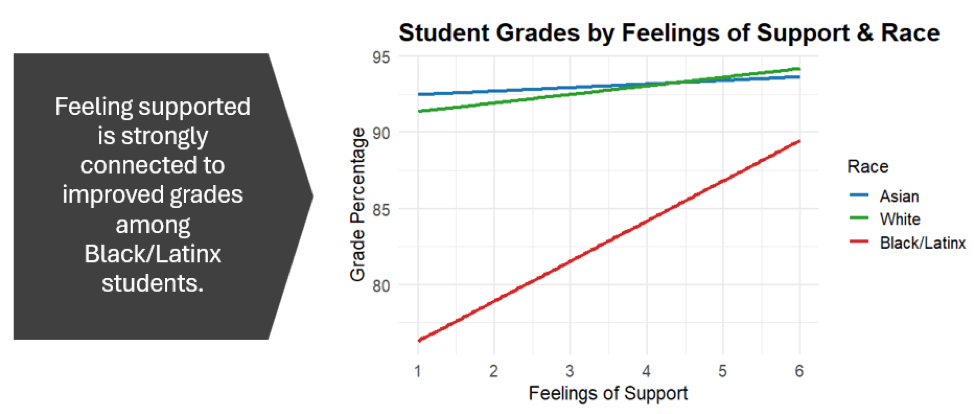

We looked at whether students’ feelings of support from their teachers were connected to their end-of-year grades. On average, students from historically marginalized racial/ethnic backgrounds (i.e., Black & Latinx) received lower grades compared to their White and Asian peers. However, when Black/Latinx students felt strongly supported by their teachers, their grades were similar to those of their peers (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Feeling supported was strongly connected to improved grades among Black/LatinX students.

Our findings in year one suggest that the PD workshop may have helped increase teachers’ orientations towards the skills and strengths that students gain as a direct function of their marginalized identities (i.e., strength-based orientations). Survey data collected at the end of the year further showed that students felt more supported by teachers who believe they gain unique strengths as a direct function of their background and identity. In turn, feeling more supported in class was associated with greater academic performance, especially among students from historically marginalized backgrounds.

(II) YEAR 2: Expanding Engagement with School Staff

In year two, we sought to engage school staff in open and honest discussions to learn more about how the university might further support their ongoing efforts to better engage with students. Overwhelmingly, school staff expressed that they would like to receive greater support translating humanizing pedagogies—like the ‘strength-based’ framework emphasized in the first workshop—into actionable strategies, practices, and activities that could be used in their classroom. Building on the success of the previous year, we developed a series of three professional development workshops that aimed to promote evidence-based strategies and practices, rooted in humanizing pedagogy, to strengthen student-teacher relationships. In addition to these workshops, we also developed an opt-in learning community for staff to further discuss, develop, and adapt these strategies for use in their own classrooms. We continued to rely on longitudinal survey measures to document the impact of these initiatives on student-teacher relationships. The timeline of all research activities is outlined in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Timeline of research activities during the second year of the RPP (year two).

Staff-Centered Learning Communities

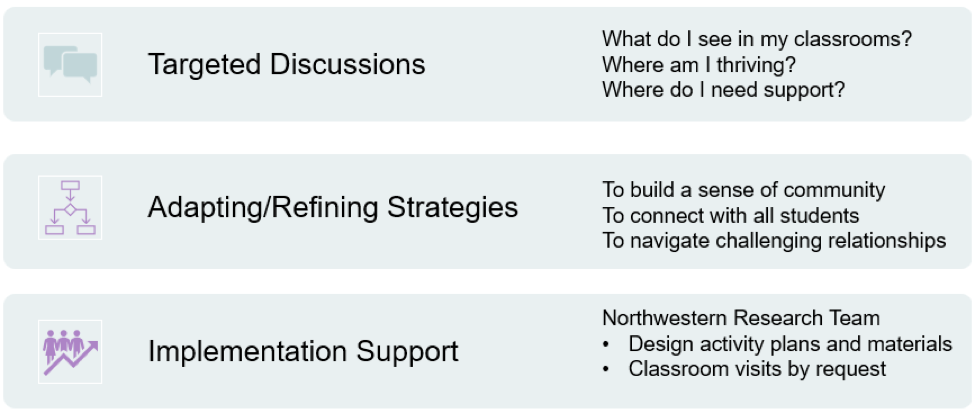

Conversations with staff informed the development of staff-centered learning communities (LCs) that focused on translating research into practice (see Figure 5). In total, 19 staff members (teachers, teaching-aids, and school counselors) participated in the LCs. Each LC consisted of 3-5 staff and 1-2 members of the research team and met twice a month. Meetings were scheduled during teachers’ planning periods. Participating staff were compensated as research consultants. LC meetings consisted of targeted discussion to share, adapt, and refine teaching strategies, practices, and activities that center students’ unique identities and strengthen classroom community. During the LC meetings, the research team communicated evidence-based research on humanizing pedagogy to inform the design and implementation of various strategies and activities explicitly designed to foster community and strengthen student-teacher relationships. Staff participating in the LC were positioned as expert practitioners to ensure that the design of strategies and activities was informed by institutional and practical knowledge.

Figure 6: The structural design of staff-centered learning communities consisted of three main sections.

The Impact of LC Participation On Student-Teacher Relationships

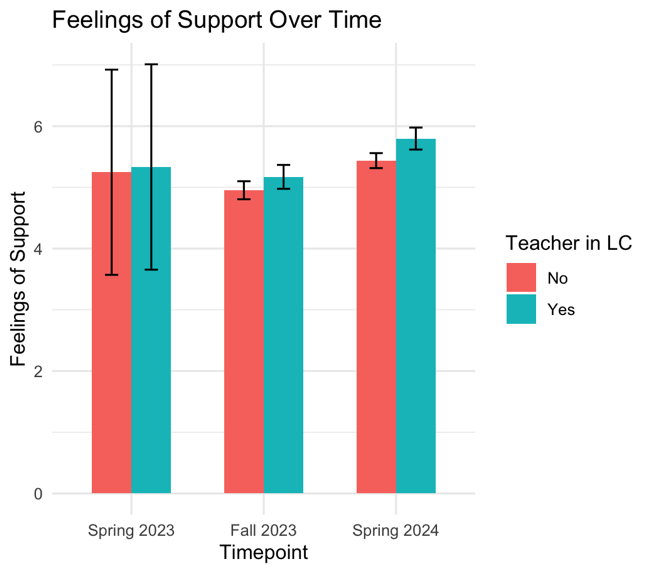

To understand whether these Learning Communities were making a difference for students, we looked at how supported students felt depending on whether their teacher participated in an LC across three waves of data collection.

In wave 1 of student data, collected prior to the development of our LCs, students reported feeling equally supported by teachers, regardless of whether their teacher would eventually participate in the LC or not in year 2. By the next wave of data collection (wave 2), collected 2 months after the development of the LCs, students reported feeling more supported by teachers participating in the LC, compared to teachers not participating. This difference remained significant in wave 3 of data collection at the end of the year (see Figure 7).

These findings suggest that the conversations, strategies, and support shared through our LCs may have helped teachers translate ideas rooted in humanizing pedagogies into actionable classroom practices that strengthen students’ feelings of support.

Even more encouraging, we saw a general rise in students’ feelings of support from wave 2 to wave 3, which may point to a broader cultural shift in the school (see Figure 7). While many factors could have played a role, it’s possible that teachers in the LCs helped contribute to this shift by sharing the ideas and strategies they developed with their colleagues.

Figure 7: Teachers’ LC participation was significantly and positively associated with greater students’ feelings of support in the 2023–2024 school year. Fall and Spring 2024 results were not significantly different but were each significant on their own.

(III) YEAR 3: Expanding Impact Through Leadership Engagement and Sustaining Change

In the third year of this work, our partner school experienced changes in leadership, but instead of this setting back our work, we were able to expand the impact of the LCs by sharing our findings with new school leadership. The collaborative infrastructure established in the previous year positioned teachers and staff to take the lead in bridging this transition in school leadership.

The new school leadership also introduced a new focus –identity-centered learning and student belonging– that highly aligned with the humanizing pedagogies our partnership focused on during the previous year. This overlap empowered staff to draw on the relationships, strategies, and data developed in the LCs to work with school leadership and the research team to co-design a scalable six-session curriculum aligned with this focus. This curriculum built directly on the strategies piloted during LC meetings and was disseminated across grade-level teams using a train-the-trainer model.

Simultaneously, the research team collaborated with school leaders to embed insights from social psychology into a new professional development (PD) series for staff. This PD series began with self-reflection on identity and social context, setting the stage for later discussions about how these dynamics shape students’ experiences at school. As a result, research and data became more deeply embedded in ongoing schoolwide efforts—not as isolated tools, but as integral components of the school’s culture and instructional approach.

As this third-year ends, we are seeing a significant shift in ownership. Teachers and school leaders are not just implementing ideas that originated from the partnership—they are actively shaping and sustaining them. The learning communities, once a small opt-in group, have evolved into a broader collaborative structure informing curriculum, PD, and strategy across the building. Importantly, school leadership is now working hand-in-hand with staff to review data, refine approaches, and set priorities for the coming year.

The transition from small cohort groups to the broader school community would not have been possible without sustained collaboration, trust, and shared commitment to equity. The NEERA partnership has shown that learning communities can serve as powerful vehicles for change—supporting teachers not only in applying research, but in leading cultural transformation within their schools.

CONCLUDING REFLECTIONS FROM PARTICIPATING EDUCATORS

The focus on understanding one’s own identity will continue to be essential for every educator—not as a one-time exercise, but as an ongoing process of reflection and growth. Teachers do not step into classrooms as neutral figures. They bring with them their lived experiences, values, and assumptions. Without awareness of their own identity, there is the risk of allowing unconscious biases to shape instruction in ways that will most certainly marginalize, misrepresent, or silence the very students that educators should aim to uplift. Due to the fact that bias is not always overt it is important to examine and confront how it might show up. It often shows up in subtle decisions: whose stories are told in our curriculum, whose voices we amplify in discussions, how we interpret behavior, and how we assess learning. These choices directly influence how students experience school—and more critically, how they see themselves as learners and community members.

Ultimately, advancing equity through community-engaged research requires more than sharing evidence—it requires building the relational and structural conditions for that evidence to take root. Through our participatory learning communities, we have interwoven this ethos into the fabric of our school work plan, with its continuation and sustainment recognized as both active and essential. This work is neither isolated nor optional. It is continuous, requiring deep reflection and vulnerability. For those involved, it asks them to examine how actions, even when well-intended, may reinforce systemic barriers already rooted in the education system. Teams must be willing to confront discomfort, to unlearn and relearn, and to remain open to accountability.

For students to truly thrive, they must feel seen, valued, and understood. A sense of belonging is not a bonus—it’s foundational to learning. That belonging must be nurtured by the adults who guide them. When teams commit to understanding their own identity and confronting bias, they lay the groundwork for more inclusive, equitable classrooms where every student can succeed.

Adrian Rivera-Rodriguez is Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Northwestern University, Anna My Truong is Destin Lab Research Assistant at Northwestern University, Mesmin P. Destin is Faculty Director of Student Access and Enrichment and Professor at Northwestern University, and Nicole Fishman is Principal at Nichols Middle School.

References

Cochran-Smith, M., & Lytle, S. L. (2009). Teacher research as stance. The Sage Handbook of Educational Action Research. London: Sage, 39-49.

Destin, M., Silverman, D. M., & Rogers, L. O. (2022). Expanding the social psychological study of educators through humanizing principles. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 16(6), e12668.

Jennings, P. A., & Greenberg, M. T. (2009). The prosocial classroom: Teacher social and emotional competence in relation to student and classroom outcomes. Review of educational research, 79(1), 491-525.

Jones, S. M., & Kahn, J. (2017). The evidence base for how we learn: Supporting students’ social, emotional, and academic development. The Aspen Institute.

Rivera-Rodriguez, A., & Mercado, E. (2024, February). Racial/ethnic collective autonomy restriction and teacher fairness: predictors and moderators of student's perceptions of teacher support. In Frontiers in Education (Vol. 9, p. 1242863). Frontiers Media SA.Sleeter, C. E. (2012). Confronting the marginalization of culturally responsive pedagogy. Urban education, 47(3), 562-584.

Suggested citation: Rivera-Rodriguez, A., Truong, A. M., Destin, M. P., & Fishman, N. (2025). Seeing and Supporting All Students Through Strong Teacher-Student Relationships. NNERPP Extra, 7(3), pp. 2-14. https://doi.org/10.25613/MF6K-CS41