PROMISING PRACTICES FOR COLLABORATIVE WRITING IN RESEARCH-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIP

It is often left to researchers and evaluators to document the main findings or takeaways of a project in peer-reviewed academic papers, even when practice-side and other stakeholders have been key partners all along the way, as is the case in research-practice partnerships (RPPs). While it may be natural for those with more academic writing experience and dedicated time for such writing activities –which tend to be researchers and evaluators– to take on the responsibility of summarizing the work, this leaves the voices and input of core RPP members up to the interpretation of other members of the team. This can dilute their input and is not in line with the collaborative and disruptive spirit of RPPs.

This article is our RPP’s story of how researchers, teacher-practitioners, and evaluators merged their varied experiences and a shared vision in a collaborative writing process that resulted in a journal article. We share our experiences of how a collaborative academic writing process can be successful if all contributing writers are mindful of the strengths, areas of growth, and scaffolds needed for each RPP member to contribute effectively. The lessons learned are not specific to our context, and we feel they can be applied to any collaborative writing scenario and be helpful for other RPPs looking to include the diverse perspectives of all stakeholders into the writing component of their partnerships.

THE PROJECT

iWonder (formerly WeatherBlur) is a longstanding web-based citizen science program facilitated by the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance (MMSA) that brings together students, teachers, and community experts as equals in the process of designing and creating science investigations relevant to their lives and communities. iWonder classrooms collaborate across regions using an interactive online platform and work together to pose research questions, share knowledge, collaboratively design scientific investigation protocols, collect and analyze data, and create action projects. From its inception, the iWonder project has valued the input and expertise of teachers to guide the development of the project, using co-design principles. During the 2021–2022 school year, evaluators from Catalyst Consulting Group concluded a multi-year project with MMSA, evaluating the ways in which a Teacher Advisory Group (TAG) of veteran iWonder teachers informed the ongoing development of the program. As we worked together, we figured out how to bring together people with different ideas, backgrounds, and opinions in a way that produced deeper levels of understanding, while simultaneously pushing each individual’s thinking and the work itself in new directions. During the course of the project, iWonder changed in significant and meaningful ways thanks to the input of the TAG. These changes included professional development, assessments, curriculum materials, web design, and timelines (and more!). All of these changes were well documented, and served as the basis for other publications.

As the project came to a close, it was clear that we had learned a tremendous amount about how to effectively construct and execute a co-design process, using the insights and expertise of both research and practice-side partners. We felt it was important to share what we had learned with a broader audience, so we set out to write a manuscript detailing this co-design process. We had two clear objectives:

- It was critical that we include all the voices that had informed the project’s co-design. To achieve this goal, we engaged five teacher leaders (TAG members) to write alongside MMSA educational researchers and two Catalyst Consulting evaluators.

- It felt natural to apply the project’s collaborative and iterative approach to the actual writing process. Because this format was already established, it felt comfortable to proceed in similar ways. From the beginning, all authors were involved in discussions regarding planning and revisions.

We outline our writing process below, with a focus on how we deliberately developed a process that would allow a range of collaborators to articulate their experiences in a way that valued the perspectives of all voices.

THE WRITERS

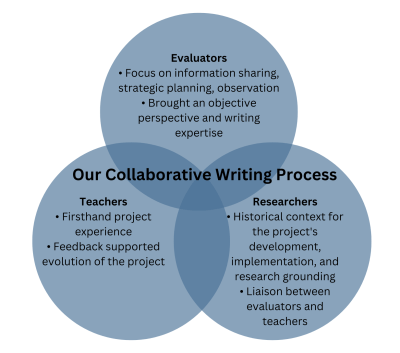

We had a group of writers with diverse perspectives, project-related experiences, and schedules. While the group members did have some overlapping experiences and expertise, each provided their own unique perspectives and contributions to the writing process. Below we describe contributions of each type of group member. The diagram summarizes these contributions and depicts what core components may be left out by excluding any of these perspectives from the writing process. Our group included the following:

- Evaluators: The lead writers. Although they had been observing and analyzing the TAG/MMSA co-design process for several years, they had not directly participated in the project. Their interactions with the MMSA staff had focused primarily on information-sharing and strategic planning, while their interactions with the TAG members were more formal. Evaluators had interviewed each TAG member several times, and observed them in video recorded professional development sessions. The evaluators were very much an external entity, and although they had become friendly and familiar with the TAG members over time, they had not interacted in ways that established relationships. As a result, the evaluators brought an informed and external perspective, and kept the group focused on the paper’s thesis. They also handled the literature review and the “deep dive” into how to make the paper fit the journal’s requirements.

- Researchers: The project leads. The iWonder leadership team included MMSA staff with deep understanding of the project’s goals and all the iterations throughout the project’s development and implementation. This group had had significant interactions with the TAG members for many years. They had visited their classrooms, provided support, and guided them through professional development. The researchers were, effectively, the liaison between the TAG and the evaluators, as they had engaged with both groups throughout the duration of the project. Having invested so much time and thought into the project, they brought with them a sense of ownership, and the skills to make meaning of all that had happened throughout the project’s journey. This group had writing experience, and was familiar with the research that we could use to support our findings.

- Teachers: The practice experts. This cohort of experienced iWonder teachers were the “boots on the ground.” They experienced the project firsthand, and were intimately aware of all its successes and challenges. Their primary objective had always been to make the iWonder experience as effective and meaningful as possible for their students and peer teachers. They had dedicated significant amounts of time to sharing their experiences and to deepening their content knowledge and understanding of the project in order to improve their students’ learning. They had fought through the trial and error stages, shared their suggestions, and brainstormed ideas. They provided communication and feedback that was essential to the project’s evolution, and they were best suited to articulate these elements in the manuscript. Their academic writing experience was limited. Their insight was invaluable.

Figure 1: Contributions to the Writing Project By Writing Group.

THE WRITING PROCESS

The following elements were critical to the success of our writing collaboration:

- Content grounded in participant experiences. The focus of our manuscript was rooted in participants’ reflections of their experience during the co-design process. Because this was something that each TAG member went through, they were able to contribute meaningfully to the content and structure of the paper. The evaluators guided the TAG through an exercise that allowed participants to summarize the co-design experience in their own words, to generate consensus about which elements were most critical to success, and to articulate these key steps in a way that a broader audience could understand. The thesis and structure of our manuscript was born from this activity. Incorporating all these factors, we created a detailed outline that served as our guide throughout the entire writing process.

- Transparency and delegation. This outline was uploaded into a shared Google Drive that all authors could access at any time. Presented as a spreadsheet, it included the headings and a brief summary of key discussion points for each section. Authors signed up for the sections they felt most compelled and prepared to write about. Each section had two authors and one editor.

- Responsive timelines. The lead writers drew upon their experience with academic writing and journal submission. Knowing the end point, they created a timeline with milestone points and check-ins along the way. This map clearly articulated each benchmark that we needed to hit in order to meet our deadline. From the first writing group meeting, we collaboratively laid out the schedule for all the writing tasks, from brainstorming to drafts to editing and final submission. We adjusted our timeline around writers’ availability. For example, teachers had more free time to write in the summer, so we designated their writing time in June–August. The MMSA staff contributed their content in May–June, and served in an editing capacity in August–October once the teachers’ sections were complete. Catalyst evaluators managed the workflow and emailed the authors as deadlines approached. As a result, all writers completed their tasks on time. Because the timelines were developed with input from all parties, writers could plan accordingly and were committed to meeting expectations.

- Regular check-in opportunities. Although we spent a lot of time up-front talking about the vision for the paper, it understandably evolved through the writing process, and we all had questions. So, we made a point of scheduling monthly virtual meetings where we could talk through the challenges and brainstorm solutions together. Sometimes these sessions were conceptual discussions. Other times they were editing sessions, with the paper in front of us. We left the structure open so that the meetings could serve whatever purpose was needed at the time.

- Well-articulated schedules. We committed to a meeting time that worked for everyone, and we stuck to the same day and time for every meeting. MMSA staff sent reminders, with specific tasks for everyone to complete in preparation for each session. Having a designated time slot created consistency, and the group became familiar with our schedule and routine. Our collective commitment to a regular check-in time resulted in high participation and engagement during those sessions. When we honored everyone’s commitment, participation levels were high.

- Respect. Once the writing was finished, the evaluators took on the task of merging all the sections together to make the paper cohesive. This involved a good deal of careful editing so that the voice, tone, and style were consistent, despite having been written by many people. Here we had to make sure not to lose the perspective of each individual author. It was challenging at times, but we did it. Because our goal was synthesis, we had to look at the entire document with an objective lens, without regard for which authors had written which sections. We had to set aside our personal connections, and not worry that our changes would hurt anyone’s feelings. (We had discussed this as a group beforehand and had come to a mutual understanding, which definitely helped with the process.) A large part of this task was to eliminate redundancies, where different authors had written similar ideas in separate sections. We also chose to remove any “I” statements or specific and/or identifying information. While the TAG teachers had significant anecdotal evidence to share from their classroom settings, we had to stay focused on the big picture. One last critical step in this phase was to create a flow that made sense. This involved significant cutting and pasting, and shifting the sequence of sections to tell our story in a logical, progressive way.

- Agreement. The manuscript was not finished until ALL authors agreed to the final product. After completing the editing process, everyone had a final chance to review the paper. We received minimal feedback, incorporated some minor changes, and sent it off to the journal with the blessing of the entire writing team.

LESSONS LEARNED

Upon completion of the paper, the writing team met one final time to celebrate our accomplishment and to debrief on the process. We all agreed that it was a positive and successful collaboration, and we shared input on how we could enhance and further streamline the process for future collaborative writing efforts. We approached this conversation very similarly to the way we had conducted all of our writing meetings. With open minds, we listened to everyone’s thoughts and suggestions. We discussed them without judgment or defensiveness and we collected them into a document that can be used for future reference. These key takeaways are summarized below.

Successful logistics that we would use again:

- Word counts are important. In the outline, we assigned word counts to each section. This enabled writers to be concise and maintain focus on their specific content. It helped tremendously during the editing process because each section was already concise.

- Color-coded organization chart. We broke the paper into sections, and then presented it as a spreadsheet. Headings for each section included thesis, word count, writer(s), editor, and timeline for completion. Each row/section started with no color-coding. Writers highlighted the section in green to indicate they had begun writing. Highlighting was changed to yellow to indicate it was ready for editing. Editors highlighted in red to indicate the section was complete. Having this visual allowed the lead writers to monitor progress, and to check in on writers who were delayed and/or struggling with a section. It limited the volume of emails and streamlined communication.

- Writing in a “live” document. Our paper lived in a Google Drive throughout the duration of the writing process. This way, multiple writers could work at the same time, if necessary, and we did not have to track changes or wait between emailed versions. We separated the sections into different documents, with the intention of making it easier to access each section without scrolling through too many pages (this part of our document organization could be improved next time – see more on this in our section on possible improvements below). Communication existed primarily through comments directly within the document. This approach allowed writers to stay focused on their assigned sections and to communicate directly with those who shared their sections. Other writers could be flagged to review or provide input as needed. All sections were available to all writers to access, read, review, and use as a reference to ensure continuity across sections and to help eliminate redundancies. Using Google Docs, we were able to check the version history at any point, which made it easy to retrieve deleted text if necessary.

- Compensation of practitioners. Our teacher writing teammates were compensated on an hourly basis for their time and expertise in contributing to the manuscript. We recognized that this task was above and beyond the original scope of their TAG member responsibilities and felt it was important to compensate them as professionals. We asked TAG members to keep track of their hours and paid them a set hourly rate equivalent to rates we pay to other professional educational consultants. We documented this agreement through a formalized contract that outlined the expectations of participation. This process allowed them to engage at a level that worked with their schedules and be paid for the time they devoted to this project, rather than a set stipend for all members.

Improvements suggested by writing team members:

- Devising a more democratic process for selecting writing sections. We initially used a “first-come, first-served” approach, but some writers were unable to access the document immediately due to the teaching schedules and felt they missed the opportunity to write about the things that they felt most informed and/or passionate about. While we accommodated them as editors for these sections so their voices were included, we could have found a better way to incorporate their perspectives earlier on in the process. Next time, we will try using one of the regular meetings to jointly negotiate writing assignments.

- Limiting the number of writers per section. We assigned two writers to most sections, and this presented a challenge, as writers had different schedules and writing styles. The more effective approach was assigning a lead writer and then a second writer who served more as an editor for that section. Our writing team suggested using this structure next time.

- Providing more guidance, specifically about academic writing. This would have expedited the editing process and taught writers how to be more concise with their ideas. While the evaluator team members did share some prior publications for authors to use as references, we could have spent some of our meeting time discussing and analyzing these articles with an eye on how our article should be similar and/or different. Next time, we will take this approach, or possibly share excerpts from other papers that could guide a conversation about why that exemplar is a good model for the type of paper we aim to write.

- Taking a different approach to document organization. Each section had its own document, as we felt it would be challenging to read through so many pages, and it can be difficult to work in a document if many other writers are writing at the same time. But this meant we had to jump back and forth between documents to understand where one section fit in with the rest of the paper. This resulted in redundancies, as different writers wrote similar ideas in separate sections, which then led to more editing work than would be required in a paper with fewer authors. Next time, we will use one Google Document for all sections and the Table of Contents feature to allow writers to jump easily from section to section within the document. Having all text in one document will also allow writers to search for key terms that have already been introduced in earlier sections. We will also add redundancy checks to our regular meetings to make sure the team is not duplicating efforts.

- Shortening the timeline. Spreading the writing process out across many months meant we had to re-familiarize ourselves with the paper each time we revisited it. This made each edit take longer, as we had to acquaint ourselves with the new content. Compressing the timeline would have made it easier to remember and keep track of our progress and thesis. The next time we work with teacher practitioners, we will endeavor to complete the entire collaborative writing process in the summer months.

Table 1: Summary of Effective Strategies and Improvement Areas for Collaborative Writing Efforts

| Effective Strategies | Improvement Areas |

| Clear communication and writing structures (word counts, color-coded writing process) | Avoid “first-come, first-served” writing assignments for more fair distribution of assignments |

| Collaborative writing in a “live document” | Limit the writers working on each section so each feels ownership |

| Fair compensation | Work towards more unified voice and consistency by organizing document sharing, shortening timeframe, providing additional writing guidance |

THE RESULT

It took us approximately eight months to complete our manuscript. While this is certainly longer than a typical writing process, it was necessary in order for us to accommodate all the factors we’ve articulated here. Our paper should be published soon, and we are happy to know that others will have the chance to learn from our co-design experience. We are also proud to tell the story of how our manuscript came to be, and how much we learned in the process. We hope there will be more collaborative writing in our future, and that our readers will embrace the challenge and apply our methods to their own approach.

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation under Award Number # 1933491.

Maren Harris is an independent researcher, evaluator, and school improvement consultant who collaborated with Catalyst Consulting Group for this project; Alexandria Brasili is a research associate at the Maine Mathematics and Science Alliance; and Karen Peterman is the President of Catalyst Consulting Group.

Suggested citation: Harris, M., Brasili, A., & Peterman, K. (2024). Promising Practices for Collaborative Writing in Research-Practice Partnerships. NNERPP Extra, 6(1), 13-22. https://doi.org/10.25613/QA7G-7H29