EXPLORING EDUCATION RESEARCH-PRACTICE-POLICY ECOSYSTEMS: A CROSS-STATE ANALYSIS

With the growing recognition of the importance of increased engagement between education research, practice, and policy (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2022, 2024a, National Science Foundation, 2024), it can be informative to dig deeper into how organizations and systems within these areas work together. Formal and informal coordination and collaboration exists between education research, practice, and policy organizations within states across the country. Yet, few cross state studies have examined the ways in which research, policy, and practice interact to support research-informed policy or practice and the roles or functions organizations play within this system. We focus on state-level systems given education policy and funding are heavily determined by state government decision-making. Examining what makes collaboration in education research-policy-practice work (or not) at the state level, we might learn more about how states can create enabling conditions for those working within these systems.

In the fall of 2023, our NNERPP team, along with NNERPP members and friends, Diana Mercado-Garcia (California Education Partners – Stanford-Sequoia K-12 Research Collaborative), Eos Trinidad (University of California at Berkeley School of Education), Laura Wentworth (California Education Partners – Stanford-San Francisco Unified School District RPP), and Kyo Yamashiro (Loyola Marymount University School of Education) conducted a cross-state analysis of the research-practice-policy ecosystems in eight states in order to develop a common framework from which to examine the systems of organizations that interact, and at times collaborate, to help research, practice, and policy work together to improve educational outcomes.

We explored two main questions:

- What types of organizations engage in states’ educational research-practice-policy ecosystems?

- What types of structures, supports, and constraints influence each state’s ecosystem?

The full ecosystem report can be found here; in this article, we introduce the framework and provide an overview of our findings and look ahead to next steps.

DEVELOPING THE FRAMEWORK

Our team’s first steps were to conduct a search of existing research literature and resources on research-practice-policy ecosystems to inform the development or adaptation of a conceptual framework for case studies of the research-practice-policy ecosystems of a cross-section of states. The review focused on three high-leverage areas: (1) the organizations directly or indirectly involved in education research, practice, or policy in each state, (2) the social structures, supports, and constraints affecting organizational action or coordination, and (3) the forces of power, influence, and politics formally (and often informally) at play in each state.

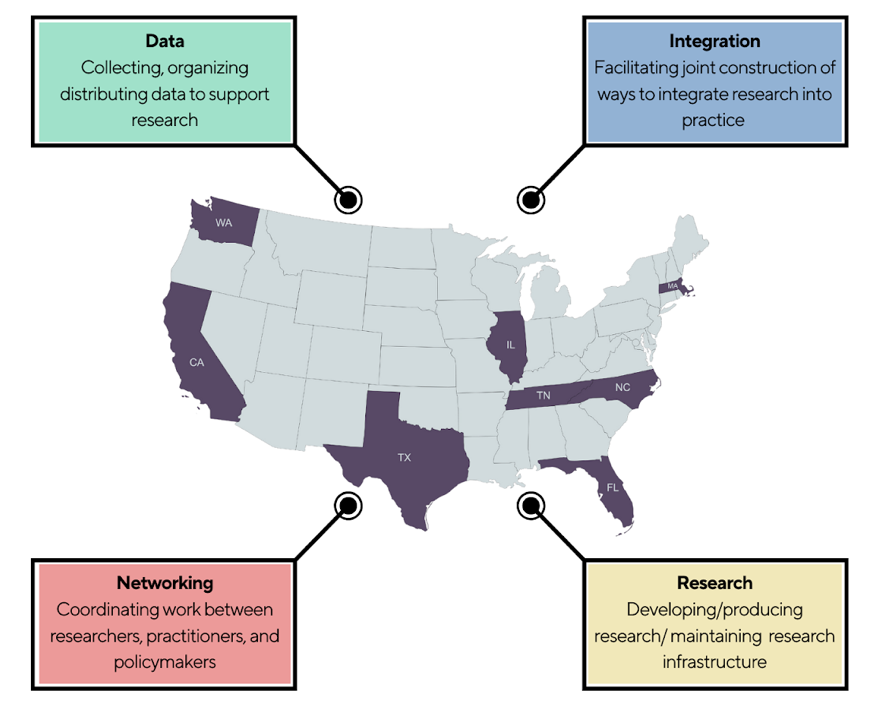

In the spring of 2024, we identified a purposeful sample of eight focus states varying in geographic region, public school enrollment, per pupil funding, and education research activity – California, Illinois, Florida, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Washington. We then conducted a review of publicly available research-practice-policy infrastructure documents and websites for each state. Following a review of documents, we identified individuals working within each sector (research, practice, or policy) in each state and conducted interviews through early summer 2024 focused on their insights on and experiences with: (1) existing research, practice, and/or policy organizations, (2) structures, supports, and constraints related to the educational research process, from funding to engagement, and (3) the ways in which power, influence, and politics work for, or against, the production of impactful education research.

Our initial framework centered mainly around characteristics of state research-policy-practice infrastructures, including centralization of governance and policy-making for research in each state and contextual features, such as political climate. Initial searches revealed variability across contexts that did not seem efficacious as a framework for enacting change, as many of our initial characteristics were highly variable, but also relatively fixed. This resulted in a shift in our focus to the functions of each structure (we identified four functions: data, integration, research, networking) and the enablers or detractors of connections across organizations with differing or complementary functions or with similar functions across different levels of a system (we identified four levels: local, regional, state, national). The idea behind the shift was that our work might produce more actionable findings and suggestions for change related to the functions of research, policy, and practice structure and infrastructural connections, rather than to simply point out systemic barriers and enablers of these systems. The figure below is a visual illustration of where our eight focus states are located and also includes definitions of the functions we explored within and across organizations.

WHAT WE FOUND

Across the four types of infrastructure roles featured in the framework (data, research, networking, integration), organizations serving as data and/or research infrastructures were the most common and well-developed across the eight case study states. Examples of structures and organizations serving mainly data purposes that were common across the states studied included “data warehouses” mainly affiliated with states’ longitudinal data systems. These warehouses are most often housed within research-intensive universities, state education agencies (SEAs), or in larger states, such as Texas, distributed across both types of entities. The presence of the data warehousing entities across each of the eight states was not surprising, given the considerable federal investments made in data and research infrastructure across all education systems in the U.S. due to federal accountability reporting requirements. Unlike the data warehouses that are most often housed within SEAs, entities serving mainly research purposes were distributed across universities and SEAs. In addition, though the data-focused entities within each state mainly work at the state level, research entities typically work at a variety of levels, including local, regional, state, and national.

In contrast to the somewhat similar structures of data and research infrastructures across states, the networking and integration infrastructures appear to be less intentionally developed across all eight states. They exist across all levels of the larger ecosystem- state, regional, and local – for a variety of purposes, and sometimes form with ad hoc groups coming together. However, across our sample states, there were few discernible patterns in what types or levels of research, practice, and policy-focused organizations served networking or integration functions, either in isolation, or as part of their larger data or research-focused work. A lack of more fully developed and coordinated efforts focused on networking and integration are possibly the result of an historically greater federal emphasis on the production of data and research, with far less emphasis and/or grant support for focusing on research use and implementation.

LESSONS LEARNED AND NEXT STEPS

From our analyses of the state cases, there emerged a set of questions to consider, which we feel could be used by research, practice, and policy entities to inform the refinement of current infrastructures or development of future infrastructures to strengthen states’ research-practice-policy ecosystems. One overarching lesson learned relates to the formation of our revised conceptual framework and the deep challenges inherent in measuring the “what works, for whom, and under what conditions” impacts of these various types of approaches and structures, including the uptake of equitable practices. Our conceptual shift from a focus on the affordances and constraints of particular social structures, incentives, and actors to a more baseline identification of the functions of several of the major structures at work in each state felt like a necessary first step as there are few, if any, tools that measure effectiveness across education research, practice, and policy ecosystems. Further interviews about the key functions and structures within research, policy, and practice within each state could help determine how the different actors think about “what works” both within and across these complex systems, beyond traditional measures of student accountability focused on standardized test scores.

In addition to a sense that more work is needed to further connect the dots about what makes for more effective research, practice, and policy infrastructure interaction across states, we were left with a set of questions that might inform future work in this area, including:

- Should a central agency or entity(ies) oversee or coordinate the various infrastructures within a state research-practice-policy ecosystem? If so, which entity or group of entities are best suited?

- When does it make sense to “outsource” the functions needed in the ecosystem to organizations beyond the State Education Agencies (SEA), Regional Education Agencies (REA) or Local Education Agencies (LEA), and when does it make sense to keep those functions in-house?

- Which organizations are best suited to take on the four types of infrastructure roles and does this differ by state context? Are SEAs, REAs or LEAs better suited for some functions over others? Which types of organizations are best suited for the less intentionally developed networking and integration functions?

- How do state data systems interact with local district data systems? And how does data infrastructure capacity vary across all districts within a state and across states (e.g., do some states support their rural or smaller districts in building and maintaining data systems)?

- When does it make sense to have a coordinated research effort that targets statewide versus regional or local research topics?

- What are the affordances and constraints of having a research infrastructure that is mostly tied to the universities in the state versus those organizations that are stand-alone nonprofits?

- How does research-producing capacity vary across districts within a state and across states?

- How does networking capacity vary across all districts within a state and across states?

- How does research integration capacity vary across all districts within a state and across states?

With increased momentum around engagement between education research, practice, and policy, research-practice partnerships (RPPs) have been suggested by many as a key means through which states might develop a more coherent system of capacity building and knowledge mobilization to support school districts (Boser & McDaniels, 2018; Farley-Ripple & MacGregor, 2024; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine, 2022). However, RPPs do not exist in vacuums outside of the states’ research-practice-policy ecosystems in which they are embedded. In order for the RPP model to realize its full potential, it is important to dig deeper into how state-level entities within states’ research-practice-policy ecosystems work together. We invite our NNERPP members and friends to explore the full paper and questions above, as well as generate additional wonderings to add to this conversation.

Kim Wright is Assistant Director of the National Network of Education Research-Practice Partnerships (NNERPP).

Suggested citation: Wright, K. (2025). Exploring Education Research-Practice-Policy Ecosystems: A Cross-State Analysis. NNERPP Extra, 7(1), 25-30. https://doi.org/10.25613/B7NW-QB21