ENGAGING PARENTS AS CO-DESIGNERS AND RESEARCHERS IN RESEARCH-PRACTICE PARTNERSHIPS

OVERVIEW

The Research Artifact

“Designing Culturally Situated Playful Environments for Early STEM Learning With a Latine Community”

By Vanessa N. Bermudez, Julie Salazar, Leiny Garcia, Karlena D. Ochoa, Annelise Pesch, Wendy Roldan, Stephanie Soto-Lara, Wendy Gomez, Rigoberto Rodriguez, Kathy Hirsh-Pasek, June Ahn, and Andres S. Bustamante (2023)

The RPP: Mission

Our research-practice partnership (RPP) unites the Orange County Educational Advancement Network (OCEAN) at the University of California, Irvine’s School of Education with the Santa Ana Early Learning Initiative (SAELI). Established in 2019, this partnership is grounded in our shared commitment to strengthening early childhood education through fostering equitable collaboration with parents and families. We engage parents as co-designers of educational artifacts and as community researchers to assess the impact of these artifacts on out-of-school environments. Artifacts reflect the local cultural values and practices while promoting early Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM) learning through play.

The RPP: History and Context of our Community Partner

Founded in 2016, SAELI has created and sustained a dynamic network of more than 300 Santa Ana, California, caregivers and residents collaborating with over 20 local elementary schools, 20 nonprofit organizations, universities, and city and county agencies to create home, school, and neighborhood environments that promote the well-being of children 0-9 years old and their families. SAELI uses a Collective Impact Approach bolstered by a data infrastructure to gauge community-level change using population-level dashboards of early childhood development data collected by First 5 Orange County. At the heart of SAELI’s collaborative work is a deep understanding of the role systemic racism and other forms of oppression around gender, class, sexuality, and (dis)ability still play in education and society overall and a shared commitment to disrupt these oppressive patterns through its work. Over the past eight years, SAELI has focused on building (a) cross-organizational collaboration to provide integrated services and supports; (b) civic leadership capacity to create curriculum and training; and (c) community organizing strategies to support Latine parent and resident-led advocacy for policy and systems change. Examples of SAELI’s capacity-building strategies include strengthening the capacity of parents and families to lead neighborhood canvassing to promote early literacy and access to services; advocacy campaigns for policy and systems change; and co-designing sessions to create school-based wellness centers and playful learning environments, among other activities.

WHY THIS WORK

Our collaboration with SAELI is part of the Playful Learning Landscapes (PLL) initiative, which recognizes that young children spend about 80% of their waking hours outside of school. Informal learning spaces, such as zoos, museums, and science centers, offer children valuable opportunities for active exploration and skill development aligned with math and science standards. However, historically marginalized children, particularly those from underserved communities, often have limited access to enriching environments within their neighborhoods, which is the case in Santa Ana. To address this disparity, SAELI advocates for the renovation and expansion of open and green spaces in Santa Ana. Building on this effort, this RPP aims to transform parks and other everyday locations that families frequent –bus stops and grocery stores– into vibrant spaces for rich STEM learning experiences through life-size games, making these opportunities more accessible and inclusive.

To do this, our RPP centers the voices, experiences, and expertise of parents and families in the co-design of learning environments. Emerging research underscores the importance of family and community-centered approaches to co-design educational programs, and uplifting the cultural and community strengths, expertise, and wealth to create more equitable and meaningful learning experiences (Anderson-Coto et al., 2024; Bermudez et al., 2024; Belgrave et al., 2022). Moreover, we believe this approach is essential to ensuring the sustainability of these powerful community-centered learning environments.

APPROACHES TO CENTERING COMMUNITY IN RESEARCH

We aimed to uncover the funds of knowledge within Latine families, primarily of Mexican heritage, who are part of SAELI. We sought to explore their values and practices related to play, science, and math learning, to integrate these insights into the re-design of public spaces, merging them with principles of playful learning and STEM education. This project began when UCI Professor Dr. Andres Bustamante connected with SAELI’s founding director Dr. Rigoberto Rodriguez who saw strong alignment with several ongoing initiatives. Dr. Rodriguez invited Dr. Bustamante to share his work with SAELI families during their general assembly meeting. Parents responded enthusiastically about bringing this initiative to Santa Ana and co-leading this process. One critical move that Dr. Rodriguez made was to invite Dr. Bustamante to join the SAELI steering committee. This positioned Dr. Bustamante as a member of SAELI instead of as an outside researcher joining for a single project. Through this partnership, we pursued and were awarded a $2.7 million award from the National Science Foundation to bring Playful Learning Landscapes to Santa Ana.

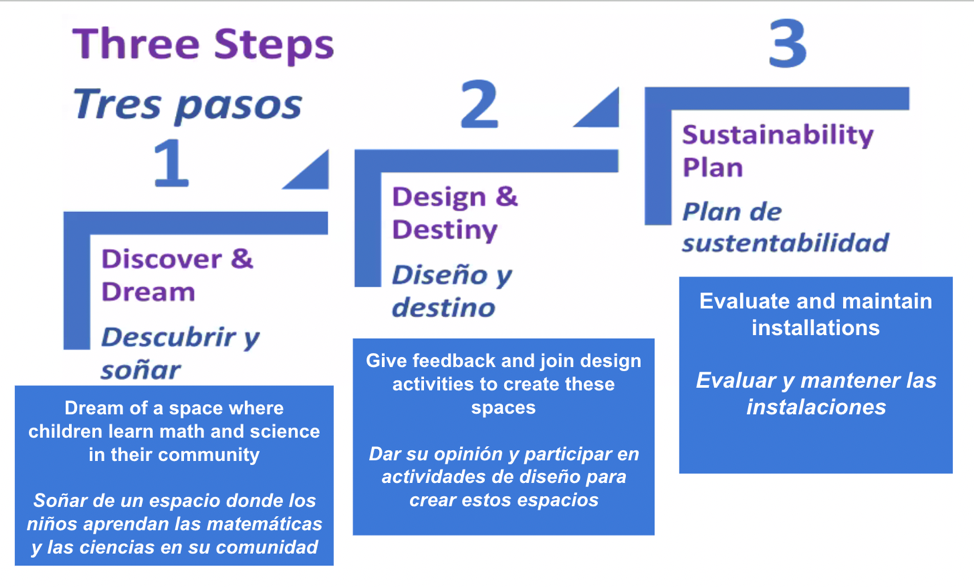

This project launched in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, which derailed many promising projects. However, SAELI had proactively arranged home visits to set up the infrastructure to engage on Zoom, which was new for many families at the time. Therefore, we were able to build on SAELI’s existing virtual infrastructure and began engaging with more than 40 parent volunteers and SAELI leaders in planning sessions, which were facilitated in Spanish to honor the parents’ language, with a translator available for English-speaking representatives from local organizations. We learned about SAELI’s unique three-step design framework: “Discover & Dream,” “Design & Destiny,” and “Sustainability” (Figure 1). Inspired by these insights, we adopted these structures into the project. For instance, during the “Discover & Dream” step, we invited parents to envision the kinds of spaces they would like in their community to support math and science learning, encouraging them to dream without thinking of constraints. In the following step, “Design & Destiny,” we highlighted their engagement in design activities to materialize their vision for playful learning spaces in Santa Ana, framing it as a collaborative and iterative process to refine the designs. Lastly, in the “Sustainability” phase, we focused on evaluation and community ownership as key to showcasing the impact of our partnership and ensuring the ongoing maintenance of the installations. Furthermore, regular meetings with SAELI’s directors became a cornerstone of our initial preparation, allowing us to align on the goals and activities for the virtual sessions that would mark the first year of our partnership.

During our first co-design session, we prioritized discussions on how this project and partnership aligned with SAELI’s mission to promote early learning and advocate for community spaces for families. We also held a transparent conversation about how the sites would be selected and provided a space for parents to share any concerns, with SAELI directors guiding the conversation and addressing parents’ questions. Parents joined from many different neighborhoods in Santa Ana, thus naturally, families hoped that the designs would be installed in their own neighborhood spaces. However, leveraging community assets like the collectivist cultural orientation that many Latine families possess, we were able to frame this project as building from existing community efforts and in service of the larger Santa Ana community. Sites were ultimately chosen collaboratively with families with intentionality towards combining efforts and resources when possible. For example, the site for our Abacus Bus Stop was selected because the City of Santa Ana was conducting a major renovation on the Main Street corridor and reached out about using our design (Figure 2). By aligning this work with an existing project from the city, we were able to expand the impact of the project and free up additional resources from the NSF grant. Similarly, we expressed to parents that these projects were meant to serve as a proof of concept and demonstrate evidence of this approach so that we could expand to additional sites across the city. With this framing, parents were ready to dive into the project without concerns for where sites would be placed.

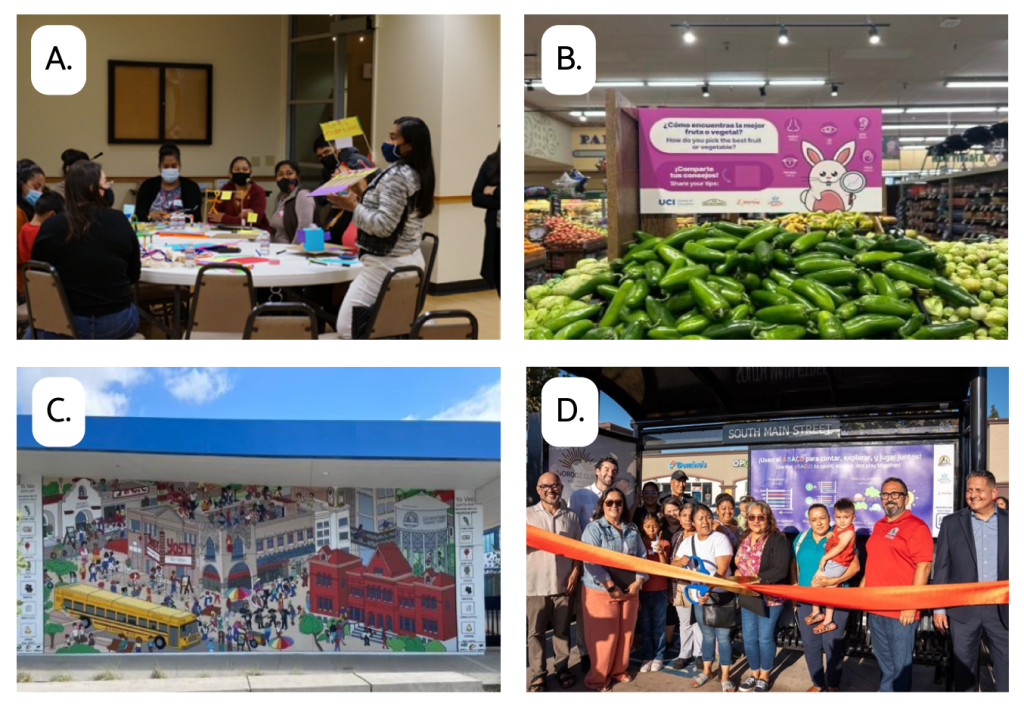

During the first year of the project, we held seven virtual co-design sessions, where we engaged with parents through various design techniques. These included storytelling prompts for families to share their everyday experiences, such as grocery shopping or preparing meals with their children and memories from their childhoods in Latin America. We used photo elicitation, where parents shared photos and descriptions of community spaces they frequented, highlighting the math and science as well as emotions tied to those spaces. Additionally, parents created prototypes of the installations using arts and crafts to share their vision for parks, bus stops, and grocery stores, while integrating community values, playful learning principles, and STEM concepts. Once we were able to meet in person for playtesting and refinement, we held an additional 15 sessions at a local community center. We began each session with a thirty-minute dinner with families, followed by 90 minutes of design activities. These activities not only enabled us to co-create designs that held meaning for families but also deepened our relationships, personal connections, and built strong relational trust (Figure 3A).

We engaged and positioned parents as community researchers to build trustful connections and ensure the research would be relevant to their community. An initial roadblock we encountered on the university-side was the university’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) requirement for extensive online training for any hired researcher. This was not feasible for the parents we worked with, many of whom do not read or speak English. After discussing with IRB, the solution was for the PI to oversee and take responsibility for everyone working on the project. Going this route, we were able to compensate parents as participants through stipends rather than hiring them, which may be difficult for undocumented parents. We invited all parents who participated in the PLL co-design process to conduct surveys with us, and 23 mothers accepted our invitation to participate as co-researchers. Parents conducted surveys (N = 256) with other parents in their community regarding their views on play and learning before the installation of co-designed PLLs at parks, bus stops, and grocery stores. Further, we asked how often the families visited the spaces and how safe they felt having their children play in their neighborhood. The purpose of this survey was to see if there would be changes in parents’ perceptions of opportunities to play and learn in informal settings after engaging with the PLL installations and whether there would be changes in the frequency in which they visited the locations and how safe they felt.

To cover important information for collecting data, we provided a two-session workshop in Spanish for the purpose of this research, the Belmont Report, informed consent, and confidentiality. In addition, we discussed how to approach community members and discussed all survey items. Parents shared tips for approaching community members, including how to introduce themselves and share about the exciting work that is being conducted with SAELI and UCI. After the pre-installation data collection was complete, we interviewed three parents to learn about their experiences in the co-design sessions and surveying community members. Parents shared they were motivated to participate because they are part of the Santa Ana community and “so that children can have positive experiences” in their community. Further, parents noted that they felt empowered engaging with their community and felt grateful for the “opportunity to work with people and survey community members”. Parents are in the process of collecting post-installation surveys and once complete, we will hold focus groups and interviews for all 23 mothers to learn more about their experiences.

FINDINGS

The various techniques we used enabled us to learn how Latine families support their children’s STEM learning and their values. For example, families practiced early math and science skills during board games and while making observations or weighing food at the grocery store. They also emphasized the value of familismo, seeking environments that fostered collaboration, family unity, and intergenerational learning. Additionally, they wanted their heritage to be represented in the learning environments we were co-creating through examples of their traditions and historical figures with vibrant art to enrich STEM education. Our collaboration resulted in three STEM signs for a grocery store, an Abacus game for a bus stop, three life-sized games –Lotería, How Tall Am I, Santa Ana Parkopolis– for two parks, and a series of I-Spy murals, all reflecting the experiences and designs of the families. As an example, the “Why’d you pick me?” sign emerged from parents’ stories about strategies they or their grandparents used to find the best produce, like knocking on a watermelon to listen for a deep, hollow sound or observing color variations to gauge ripeness – rich scientific practices (Figure 3B). The sign encourages families to use their senses to find the best produce and to share those tips with others. Parents also noted that Santa Ana lacks green spaces and explored ways that we could leverage walls, leading to the idea of painting murals to activate learning in those spaces. The “Yo Veo” or I-Spy mural (Figure 3C) that promotes spatial development resulted from families’ desire for a representation of Santa Ana, providing direct input on the landmarks and activities they wanted to see included.

Key themes that emerged from parent interviews about their experiences in the design process were: (1) enjoyment of the activities, (2) feeling valued and welcomed, (3) a strong motivation to contribute, driven by a desire to support their families and community, and (4) a sense of pride in their contributions and ownership of the outcomes. One parent, for instance, shared: “I felt like a teenager, like a girl, because we think, remember, and draw, and maybe in other moments like we are mothers we don’t do it, but I like this space because we explore, think, draw, so I am grateful to each of you.” Other parents used phrases like “family-like environment,” “we are being considered and valued,” and “you are taking into account our voices” to convey a deep sense of belonging.

At the ribbon-cutting event of the Abacus Bus Stop, attended by families, researchers, school board members, and city officials (Figure 3D), a parent expressed the emotion behind seeing the life-size installation and her eagerness to share about the project with others:

“Talking about the Abacus chokes me up because I believe it was one of the first resources that served us in our education. Now that it is here, displayed in a larger format, it is very exciting. I was explaining to my child how we used it and what it was for. I am very happy and proud to share a part of my education that helped me… I will try to walk this route more often to explain what the project is and why it matters. As I said, it’s a dream come true. I was very excited when we were told: This project will be here. I have worked on many things, but it is rare to see them realized.”

We also discovered the powerful impact of involving parents as community researchers. They successfully encouraged community members to participate, completing surveys at a rate that greatly outpaced previous researcher-led efforts. Furthermore, parents felt empowered and more confident speaking with other community members. Their conversations extended beyond the survey, addressing the need to reclaim parks for families and sharing information about organizations like SAELI. One parent shared, “I tell them, there are associations and neighborhood groups that want and can make a difference with your voice, your presence, your participation,” showing that parents went beyond doing research to promoting civic engagement.

IMPACT

Building on SAELI’s strong foundation, this RPP exemplified the transformative power of centering parent and family voices, cultural experiences, expertise, and leadership in the co-design of community spaces. This partnership has since extended to include other co-design projects focused on smart playgrounds, mobile apps, and home activities to promote early STEM learning. The collective success of this RPP has helped secure additional external grants to equip and sustain SAELI’s leadership and capacity to manage and facilitate this unique collaboration to achieve the shared vision of improving early learning outcomes in Santa Ana, CA.

NEXT STEPS

Our focus now shifts to gathering post-installation data and continuing to collaborate with parents to understand the full impact of our work. We will use a wide range of methods –naturalistic observations, video recordings, and surveys– to assess the impacts on families’ math and science practices, how the installations promote cultural expression, and shifts in community perceptions of play and learning. Parents will continue to be involved in data collection and will be invited to participate in community check-in discussions to ensure valid interpretations of qualitative data. Future interviews with parents will help us capture how this partnership elevates the voices of families and share further insights on approaches to engaging families in research. We look forward to our continued work together!

Vanessa N. Bermudez is a Ph.D. Student working with the Orange County Educational Advancement Network (OCEAN) at the UCI School of Education; Adam M. Lara is Associate Director of Research-Practice Partnerships at OCEAN; Karlena Ochoa is Assistant Professor at the California State University, Fullerton; Leiny Y. Garcia is Postdoctoral researcher at Duke University; Annelise Pesch is a Postdoctoral Fellow at Temple University; Maria J. Anderson is a Ph.D. Student working with OCEAN; Julie Salazar is a Ph.D. Student working with OCEAN; Kathy Hirsh-Pasek is Professor at Temple University; June Ahn is the Founding Director of OCEAN and Senior Associate Dean at the UCI School of Education; Andres S. Bustamante is Faculty Director of OCEAN and Associate Professor at UCI School of Education; Wendy Gomez is Director of the Santa Ana Early Learning Initiative, and Rigoberto Rodriguez is the Founder of the Santa Ana Early Learning Initiative and Associate Professor at the California State University, Long Beach.

Suggested citation: Bermudez, V. N., Lara, A., Ochoa, K., Garcia, L., Pesch, A., Anderson, M. J., Salazar, J., Hirsh-Pasek, K., Ahn, J., Bustamante, A. S., Gomez, W., and Rodriguez, R. Engaging Parents as Co-Designers and Researchers in Research-Practice Partnerships. NNERPP Extra, 6(4), 2-10. https://doi.org/10.25613/93AV-WF30